Is Tolkien Old-Fashioned? What Happens when Substackers Dissect “On Fairy-Stories.”

Pt. 5 on Tolkien’s Esaay: Highlights from the Community

We’ve come now to the end of our series on Tolkien’s “On Fairy-Stories.” Though there’s undoubtedly lots more to unpack in the essay itself, we feel we’ve sufficiently introduced the main, enduring ideas of the piece: on Fantasy, Recovery, Escape, and Consolation.

(If you want to catch up, you can start with part 1 here.)

We’ve had a blast writing this series for you all, but it’s been even more fun to engage with the insightful members of our Substack community, so for our final post, as promised, we want to share a host of responses that drew out things we hadn’t noticed, challenged us to think more deeply, or else just explored themes we’d only lightly touched upon.

As we go, we’ll link to comments or Notes from the community, or else we’ll quote them for brevity’s sake. The two of us will add some thoughts of our own in some places; Cliff’s words will be italicized, and Eric’s words will be normally formatted.

This is meant to spur more discussion, so hop into those posts’ threads, drop into the comments below, tag each other on Notes, share this essay around, and let’s get chatting!

What Is Fantasy, Really?

The first shout-out goes deservedly to

, who took the time to thoughtfully engage with every one of this series’s four pieces. From part 1, Mark sparked an insightful debate around a simple question: “how do we define fantasy as a genre, anyway?”I would say the fairytales and fantasy are two distinct genres, and that while Lord of the Rings birthed the fantasy genre, it does not actually belong to it. It is a fairytale.[...]

Modern fantasy, I would suggest, took LOTR, stripped out the fairytale elements, and hybridized it with science fiction. The result was to replace virtue with competence at the heart of fantasy. Competence has always been the heart of science fiction. It has become the heart of fantasy also, with highly defined magic systems and schools of wizardry. [But] The landscape of faerie is thus fundamentally moral. (link to original comment)

Cliff: I think we have to acknowledge when reading Tolkien’s definitions of Fairy Story and Fantasy that the genre has seismically changed. Part of that is Tolkien’s doing, and part of that is the doing of thousands of authors, publishers, and agents and millions and millions of readers. Tolkien’s Fairy Stories aren’t even really the modus operandi anymore. We’ve seen such a huge diaspora of Fantasy literature since his time. And I think we almost have to acknowledge Fairy Story as its own subgenre on the Fantasy shelf but still separate from Fairy Tales.

So my question for Eric is, when Tolkien thought of “Fairy Stories,” what are a few key characteristics that would have separated what he was imagining from how we think of the Fantasy genre as a whole today?

P.S. Thanks for writing the first installment and tackling this topic. It looked like a ton of work, and I’m so glad I could just read what you wrote. ;)

Eric says: As you know, the realism of fantasy worldbuilding is something I think (and write) about quite a lot, so tackling that section was a delight.

As for your question, I genuinely find it hard to answer, because I see our thinking as so fundamentally different from Tolkien’s. One could argue that “genre” fiction did not even fully exist yet in the 1940s, except the early forays into sci-fi (which Tolkien mentions). He spoke about fairy-stories as being like myth but also distinct, like folklore but different, in the realm of general narrative storytelling but a discrete Artform all its own… The word “genre” does not appear in the essay even once. That’s so foreign to how we think of it, I’m not sure we can point to any one thing. We, on the other hand have genres and subgenres.

To Mark’s point, I think fantasy (and fairy-stories, and myth, etc.) are all categories that have a rotating core of features but no one work will have them all, which means that choosing any one thing as a necessary characteristic inevitably excludes pieces of fiction that most people, on the balance, would include. I hold that “fantasy” is an amorphous category, and while I believe it has value that is distinct from other fiction, even sci-fi, I struggle to hold a single prescriptive definition beyond “has a magical otherworld.” I admit there’s a bit of cognitive dissonance there I’m still trying to flatten out: I think it is NOT just aesthetics, but I find every definition prescriptive; we end up using the word differently than the rest of the world which is… not helpful.

That’s why I like Tolkien’s Cauldron image; there’s a whole lot of ingredients in the Soup, and every spoonful tastes a bit different. Myth overlaps with folklore which overlaps with fairy-stories which overlaps with fantasy. But I don’t consider ancient myth and fantasy to have much in common except when the latter is designed to recall the former.

All this to say, if I had to try to figure out what “key characteristics” separate what Tolkien calls “fairy-story” from we call “fantasy story,” I’d hazard the following:

A rootedness in folklore, which has a collective sort of authorship, disappearing back into the mists of history

A fractal quality, which seems to inspire and spawn more stories

A tendency to depict or rely on archetypes without writing derivatively from archetypes

A moral quality of some kind.

Again, its not that “modern fantasy” can’t have these things. But in the Venn-diagram/spectrum between fairy-story and fantasy, I’d put these things closer to fairy-story.

Meanwhile, commenting on Part 4 of the series,

asks a very worthwhile question that’s relevant here:Do we even need a philosophy of fantasy anyway? Why do we fantasists keep feeling the need to defend our chosen mode of storytelling by demonstrating how it serves some greater purpose? Do other genres engage in this kind of apologia -- I'm asking seriously, because I really have never read much lit crit about other genres.

I don’t really know the answer! I see similar discourse around horror, sci-fi, and sometimes around literary fiction when authors get down about money and begin to question their purpose in life (as we are wont to do). In the end, though, I have to sort of shrug and echo something Stace herself said in a later comment:

I may not think fantasy needs defending, but I do want to know why I like it so much more than "normal" fiction!

Same, Stace. Same.

Fantasy & Imagination

We ought to give a shoutout to

who took a quick idea from this section of the series and explored it more fully. Tolkien says that Fantasy can only happen within Imagination, and therefore the written word is the best form for generating it. Tolkien says no other artform can do it (although he also walks that back a little even within the essay).Anyway, G.K. explored that question and makes great points about the additions that visual media and music can add to elements of true Fantasy. You can read that post here:

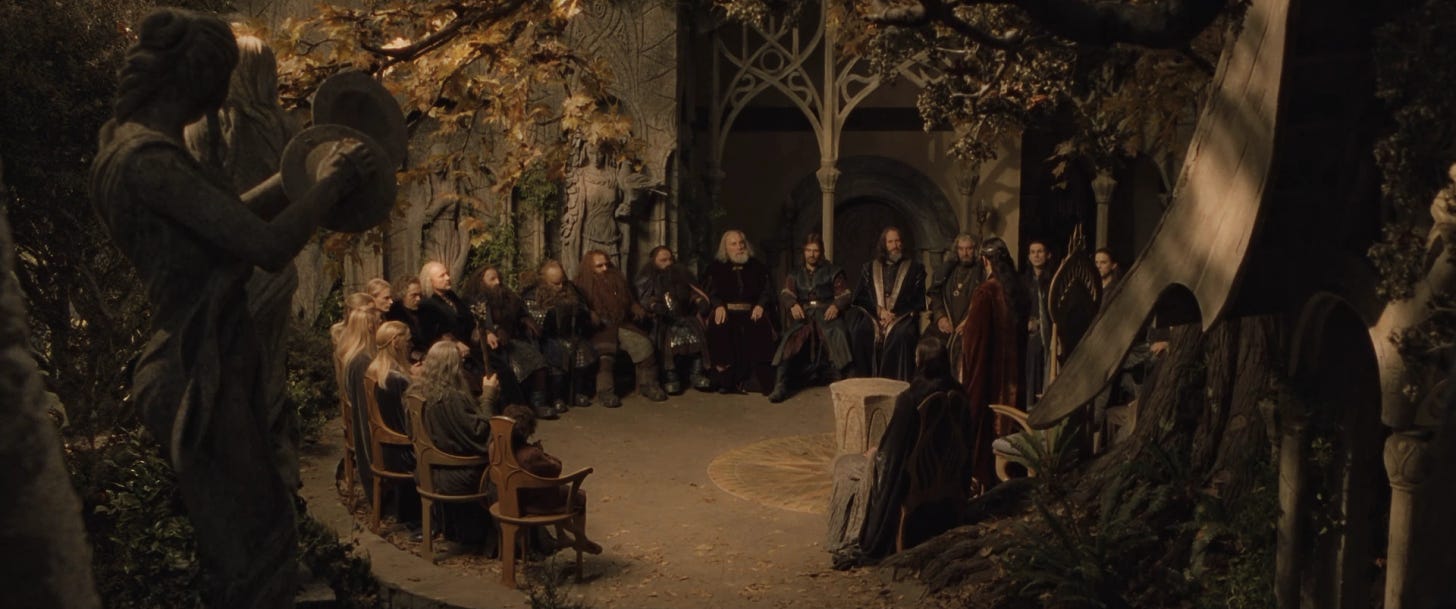

It is a great exploration of a topic we didn’t get a chance to cover in depth; to me (Eric), it also helped show the fact that Tolkien’s thoughts were trapped partly by the 1930s media-context in which he first wrote OFS (where radio was the highest-tech thing around. Rudimentary TV was still two decades in the future….)

Responses to Recovery

On Recovery,

helped us think about other ways, besides fiction, to recover the sense of wonder that we might’ve lost:I wonder if, in addition to the technique you describe, something else can Recover and re-mystify the world. If what you’ve described requires seeing the person, place, or thing in a renewed way, gratitude helps us see the whole context that way. Ingratitude and demystification seem to go together. (original comment)

Cliff says: I really liked what Josh said about gratitude being another option for remystifying the world around us. While it works differently than fairy stories, gratitude prepares us to appreciate the good and wonder in the things we are grateful for. It keeps us from being dulled to what’s around us.

Eric says: Agreed. It’s not one or the other, of course. Gratitude is a choice, often enough, and we have to deliberately cultivate a sense of gratefulness and humility in order to receive things—to receive anything—as a wondrous gift. But what if we don’t make that choice?

That’s where the fairy-story comes in: through the experience of the story, the reader can find himself “recovering” wonder for the ordinary world even, perhaps, against his own will. That’s the hope, anyway.

Children are better at seeing the world in wonderful gratitude. That’s one thing that Tolkien writes a lot about in OFS that we didn’t cover at all. Children are more naturally able to live in a place of wonder and reception, which is why fairy-stories were thus “relegated to the nursery,” even when adult propriety began to demand cynicism and materialism. But of course it’s we cynics that need fairy-stories the most. It is people like me who need to recover the sense of wonder and, yes, gratitude.

Elsewhere in the comments, we had another insightful addition from G. M. Baker, which I’ll let Cliff summarize and speak to:

Mark makes two points I want to respond to here. First, he reminds us that the world is not dulled for everyone and that for some people, the world is too “loud and bright.” He writes, “And this may explain why I have no taste for most modern fantasy. It is trying to turn up the volume on the world while I want to turn it down.” It’s hard for me to relate to this sentiment in a world of garishness and social media and notifications and computer screens and responsibilities and rushing around to get things done. But I will say that if you can’t find something to strike wonder into you in our world, you are not looking hard enough. The Grand Canyon is only a few hours from where I live, and the sight of that is dumbfounding and awe-inspiring. But you don’t have to go that far. I think an easy step towards recovering the awe of something is to learn about it. The more you know about something, the more you’ll understand it and then the more you’ll respect it and then love it and then be in awe of it. If you’re really finding it hard to find awe in your daily life, you’re too busy and need to start by learning about the things you take for granted. It sounds like Mark might already be doing that.

Mark’s second point, without using the exact word, is that Tolkien and Lewis lived very privileged lives of academics and tend to complain too much about wishing things were like they were in the olden days. They had their fair share of difficulties also. Tolkien lost both parents by 12, and Lewis lost one as a young child and was never close with his father. They both served in the trenches in World War I and lived through World War II. But I agree with Mark that it strikes me as a tad myopic when Lewis or Tolkien complain about industry and technology without acknowledging the lives saved and the people helped. Yes, a car does shorten the sweetness of a journey, but it also gets a doctor to a patient in time to save a life.

On the same article, ChaoZ commented:

I have recently experienced demystification too, as I was rereading the Eragon series - which I had loved as a child, it had brought me so much joy as well as creativity, love for fantasy and story ideas. Now I don't feel that anymore. I still strive to somehow love fantasy as much again.

Cliff says: I really felt for

’s comment because I too had books I read as a child that did not stand up to re-reading when I was older. And I’m not talking about outgrowing them. I’m talking about books that were just plain dumb that I didn’t realize until I was older–The Hardy Boys being the chief offender. Seriously, how many hobbies was Chet going to have? And they always got captured at the 80% point. And there was always a fist fight with the villains right before the book wrapped up. It was predictable and lazy, and it had little literary value of any kind.I think books that stand up to re-reading best and that maintain their mystique are ones that are (A) written well, (B) written with deeper themes in mind, and (C) written around complicated and interesting characters. I don’t think either The Hardy Boys or Eragon check all of those boxes. If a person has grown out of these, it’s time to dig deeper and find something more powerful.

Eric says: Once the magic that drew us to something has dried up, it can be really hard to go back. Sometimes (like with the Hardy Boys) it isn’t worth it. But I’d encourage anyone like ChaoZ, who desires to love something that they’ve become demystified with, to consider what they loved specifically about that thing in the past. Why did it speak to you? What gives you that feeling now? There are probably other ways to scratch that itch… and other fantasy works that you will love just as much now as an adult, even if for different reasons.

The Value of Escape

Two comments to cite that came from the piece about Tolkienian Escape. First,

put out this note that I think sums it up for a lot of us when it comes to Tolkien, or to our first brushes with the fantastic:Got a lump in my throat over this essay this morning (about another favorite essay.) Someday, I’ll write something about how Tolkien’s fantasy world has had very real importance to my real life and my own not very fantastic writing (at least, my post-industrial landscape is nothing like Middle Earth, though I think there are some whiffs of romanticism in my book that will annoy some sectors, probably, lol.) But today, I was mostly moved that what he set out to do with his writing he DID do in such a powerful way. I’ll never be Tolkien, but it’s something to aspire to.

Who else feels that way? 🙋♂️

Meanwhile, a comment from Cliff: As I was reading through Tolkien’s words on Escape and Escapism, I think I found where Ursula K. Le Guin copied some of his ideas. In her essay “It Doesn’t Have to Be the Way It Is,” she defends Fantasy as an escape to something better rather than as an escape from our responsibilities. I love UKLG so much, and I love her more now that I see how she was actively embracing her Fantasy Intellectual heritage from Tolkien.

Eric says: … I should really read more Le Guin …

asks a good question about how to separate the Flight of the Deserter from the Escape of the PrisonerI do feel very sympathetic towards the deserter. Why are they running from reality? Why have they rejected it and sought to lose themselves in another world that has no direct bearing or impact on their return to the real world? What about the deserter’s flight drew them over the prisoner’s escape? I did very much appreciate how well you explored the conditions an escapee might find themselves in, from the challenges of the day to day to the horrors of war - it’s a huge range of experience and need, to be sure.

Cliff: A good question and one common to Postmodernity. I don’t know Monique’s worldview, but I will address the social context that gives rise to the current popularity of Escapism. We live in a (more or less) post-truth world that more often than not accepts the natural world and denies the supernatural. If the natural world–a war-filled, dangerous, harsh, disease-and-sorrow-ridden place–is all there is, then we’re essentially very developed animals, and a natural instinct to animals is to avoid pain, and if Escapism (or anything else) accomplishes that, then it’s actually a good thing. And thus something that Tolkien was trying to defend Fantasy against–accusations of Escapism–have actually become a celebrated aspect of the genre.

Eric says: My reply at the time was basically that it depends on whether you run towards something Good or something Evil, and this is based on my reading of Tolkien’s essay. The child running into the arms of his mother and the alcoholic pounding vodka are both running from pain, but one seeks to ground themselves in a real love, and the other seeks to oblivion. The question isn’t the pain, but rather our response to it.

But what do the rest of you think? Where do we draw the line? Where does reading a good book fall on that spectrum? What about a bad book? How much does a person’s own circumstance matter for the situation? Food for thought…

Happy Ends, Their Necessity & Eucatastrophe

Now we come to the final and—if the number of comments are any indication—the most controversial of the four topics: consolation, happy endings, and eucatastrophe.

We saw more worthwhile comments from

, , and , each with varying opinions and thoughts on the subject. The conversation revolved a lot around whether eucatastrophe is really required for fantasy, how faith and worldview impacts a reader’s reaction to a happy ending (or its necessity), and how all that plays into narratives at large.There’s so much more to unpack in all of that, I wish we could represent more of that conversation here. So go to that comment section. Dive in!

You’ll also see there

making an excellent comparison between LOTR and Avatar: the Last Airbender, referring to Iroh and the White Lotus secret society. He points to this as the sort of moment that separates the darkness of things like A Song of Ice and Fire from the darkness present in Middle-Earth:You get this overwhelming sense that the protagonists aren't alone; that the path to victory has been being paved for generations before them, and they will have help on that path.

In Martin's worlds, there is *no one* like that. No one lives for a virtue greater than power without being punished for it, because ultimately no two people believe enough in virtue to put it out in front of them and cooperate towards that virtue's fulfillment. Someone always ends up betraying the Good in the name of personal power. In Tolkien, too, the number of people who live towards the Good for its own sake is very, very few... But the point is that they do exist. And part of the serendipity / Providence at work in LOTR is that these few people manage to find one another.

Then we had both

and both cite Tolkien’s own Children of Hurin as a counter-example to Tolkien’s own essay! If fantasy needs to have happy endings how do you explain that?Eric says: I’ll fall back on my idea that things like eucatastrophe aren’t necessary for fantasy, but are instead things that fantasy can do best. Tolkien upholds eucatastrophe as the opposite to tragedy (as opposed to tragedy’s other opposite: comedy); tragedy is sad-ending, but more than that it is a sorrowful ending due to inevitable premises of the story itself (often a “tragic flaw” of a “tragic hero”). So beyond merely happy/sad endings, eucatastrophe embraces this “inevitability” except towards the final, happy ending. Fantasy is at its best when it does this. Or so I take Tolkien to say. Fantasy stories can do tragedy just fine, as evidenced by Children of Hurin, but nothing can do eucatastrophe quite like fantasy.

I’m willing to bet Cliff disagrees with me, so he can have the final word on this.

Cliff: I think I’m with you on this one, Eric. We saw a split in commenters between those who thought Tolkien was way off–happy endings are overly simplistic!--and who only wanted happy endings in Fantasy–why read it if it doesn’t end happily? I think the best resolution to the debate is to acknowledge that Tolkien was writing a very specific type of Fantasy–almost a subgenre. And in his subgenre, happy endings are normal. Since then, the Fantasy genre has expanded, and tragedy is a welcome aspect, but in his literary context, he might have asked what the point of imagining another world that only brought sorrow would be. Plenty of sorrow in the real world! Fairy Stories were an avenue to discover joy. But, yes, he acknowledged that sorrow had to be part of that world–Children of Hurin–but even that is a lead up or a background to the joy that would come.

I think what wrote is a great way to conclude the discussion of Consolation:

I loved this post. Tolkien imbued fantasy and adventure with transcendence. The reader was allowed to infer powers beyond the visible world, that there was a creative good moving through Middle Earth and its beings. I guess my favorite quote is the following from The Return of the King ( I pasted from Goodreads for convenience)

“PIPPIN: I didn't think it would end this way.

GANDALF: End? No, the journey doesn't end here. Death is just another path, one that we all must take. The grey rain-curtain of this world rolls back, and all turns to silver glass, and then you see it. (original comment)

Thank you, from both of us!

That does it for this series, everyone. A big thank you to all of you, our readers, especially those who took the time to share and thoughtfully engage with our work. We couldn’t include every thoughtful comment, but we really do appreciate all the time you’ve taken to engage with us in this series.

Thank you again for reading, and for making this series such a blast!

We said it before, but if you’ve enjoyed this series and want to see more from me and Clifford, subscribe to our publications. You can sign up for Falden’s Forge at the button below…

… and as long I haven’t mucked up the settings somehow, there should be a similar button for Clifford’s Past the Dragon here just a little further down…

You also might be interested in the following posts from us both, on some similar topics:

One can also point out that Turin is part of the doom that fell on the Noldor for the Kin-Slaying, but in the end, the Valar came to the aid of Middle-earth. There can be tragedies IN a tale that ends happily.

In my short time here on Substack, I came to notice that my own thought on literature in general, and the fantastical in particular, was heavily influenced by two books: Lewis's "An Experiment in Criticism" and, of course, J. R. R. Tolkien's "On Fairy-Stories". I found myself quoting this last one so often that I thought, hey, I should just write about it already.

Then Eric and Clifford came out and wrote it first; and I've never been so happy with being late. They covered "On Fairy-Stories" much better than I could. But I'm glad that I got to contribute a little bit to the discussion.

Good job, mellyn.