I ought to begin with a thank you and a shoutout to

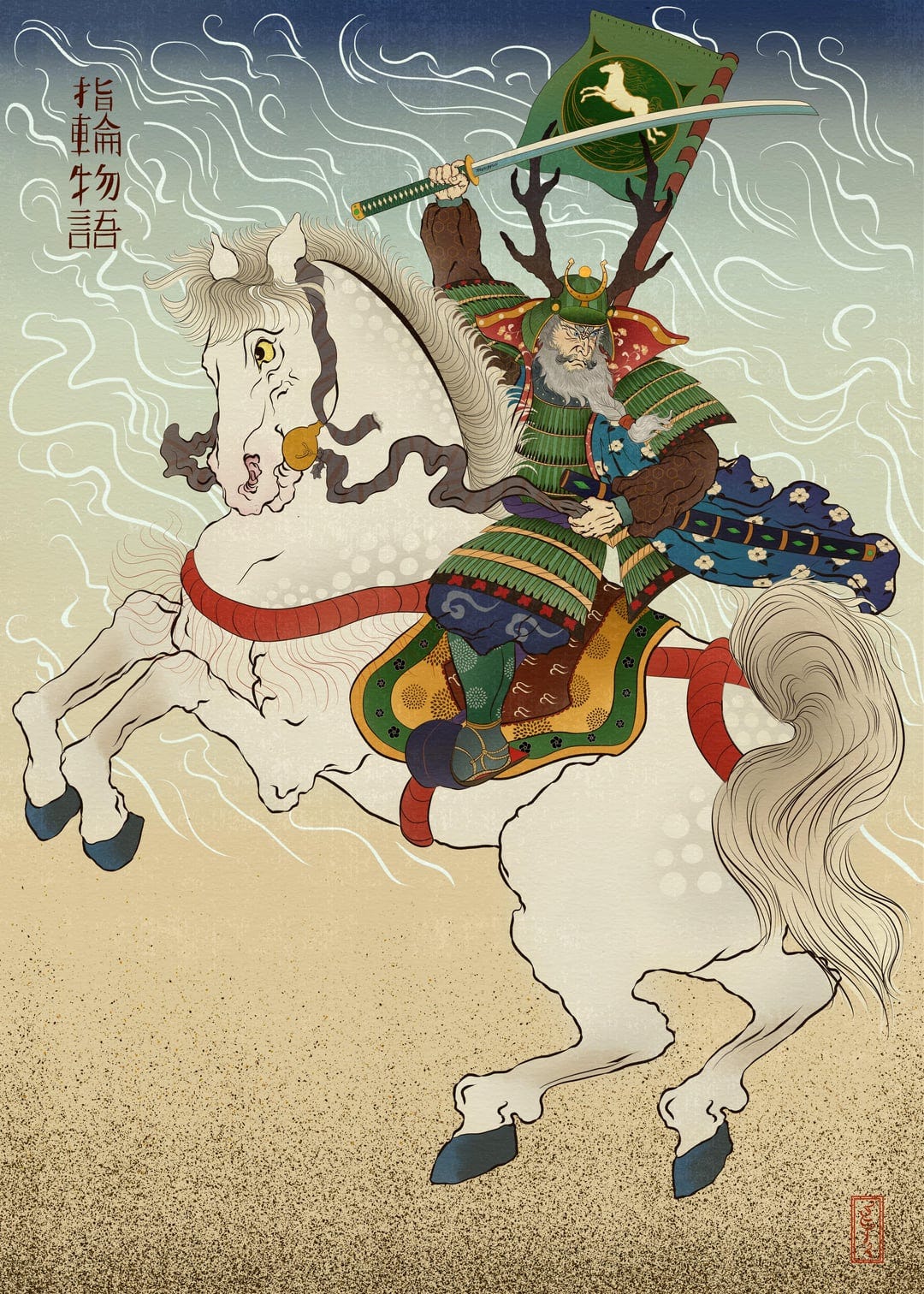

and his ongoing series about the characters of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, and, in Dan’s words, “why their choices make them all the more rounded and relatable.” At time of writing, Dan’s got two posts, on Theoden and Boromir; both are worthy reads.His first piece on King Theoden stirred up some dormant feelings in my heart, partly by his able treatment of the character but largely just from a reminiscence about my own experience with the character. I said that I’d love to write an essay on Theoden myself. This is that essay.

There’s a few things I want to do here.

First, I want to explore why I love Theoden so much, possibly above every other character in Lord of the Rings.1

Second, I want to prove that Theoden is much smarter and much braver than most people think—especially given how he is portrayed in Jackson’s films.2

Third, I want to look briefly at why Theoden got such poor treatment in Peter Jackson’s movies.

I’ll try to weave all three of these together throughout this essay. Let’s charge in.

From Darkness to Light

Theoden’s entire arc and purpose within the Lord of the Rings is laid out in his introduction and his initial encounter with Gandalf the White. What transpires over the first pages are, in effect, something that will happen over and over until Theoden reaches the end of his tale.

When we first meet Theoden, he’s a character beaten-down by the looming evils across Middle-Earth, made all the more tragic by his ignorance of that fact.

Tolkien writes:

Upon [the throne] sat a man so bent with age that he seemed almost a dwarf; but his white hair was long and thick and fell in great braids from beneath a thin golden circlet set upon his brow. In the centre upon his forehead shone a single white diamond. His beard was laid like snow upon his knees; but his eyes still burned with a bright light, glinting as he gazed at the strangers. [...]

The strangers saw that, bent though he was, he was still tall and must in youth have been high and proud indeed.

In many ways this intro is underwhelming. This king is old and bent, so much so he seems hardly a man at all.

It’s all the sadder because Tolkien precedes this introduction with several clues about the kind of king we ought to expect in Theoden; the strangers—Gandalf, Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli—see Theoden’s home, Meduseld, the Golden Hall, first. The Hall is wreathed in gold and glinting in the sunlight. The city of Edoras sprawls below it in the shadow of the mountains. Outside Edoras are sixteen burial mounds “where the sires of Theoden sleep.”

‘Seven mounds upon the left, and nine upon the right’ said Aragorn. ‘Many long lives of men it is since the golden hall was built.’

‘Five hundred times have the red leaves fallen in Mirkwood in my home since then,’ said Legolas…

Then, just as our main characters enter Meduseld, they see a huge tapestry that alone is lit by sunlight in the dark hall: an image of Eorl the Young, the forefather of Rohan; he is astride his horse, blaring his trumpet, charging into battle. Aragorn, especially, points it out to his companions.

So what should we expect from the King of the Golden Hall? What should we expect from the son of Eorl the Young and Brave? From the King whose fathers have held these gates for five centuries?

Not this.

There are hints of Rohan’s grandeur buried in Tolkien’s description of Theoden. The circlet and pure diamond, the proud braids of a warrior… but it is all lost in the affect of old age and decay.

In the moment that follows, of course, Gandalf frees Theoden from the grip of Saruman’s puppet Wormtongue, who has poisoned his mind. Jacskon’s scene here is phenomenal—who can forget it?

In Tolkien’s original telling there’s a constant interplay of light and darkness. Meduseld is bright from the outside, but dark within, except for the one beam of light upon Eorl’s tapestry. When Gandalf uncloaks himself, darkness overtakes everything until only Gandalf is visible.

The whole image is a symbol of Theoden’s own despair, and the hope that crashes into him and demands to be considered. Gandalf says:

Take courage, Lord of the Mark; for better help you will not find. No counsel have I to give to those that despair. Yet counsel I could give, and words I could speak to you. Will you hear them?

Choose hope, and act. Or else sit in despair. That is Theoden’s choice from the instant we meet him.

Theoden gets out of his chair and light begins to return to his home. He walks with Gandalf out of the hall and begins, with help, to unravel his own despair. Gandalf invites him to gaze out on his own lands, to “breathe the free air again.”

‘It is not so dark here,’ said Theoden.

‘No,’ said Gandalf. ‘Nor does age lie so heavily on your shoulders as some would have you think. Cast aside your prop!’

From the king’s hand the black staff fell clattering on the stones. He drew himself up, slowly, as a man that is stiff from long bending over some dull toil. Now tall and straight he stood, and his eyes were blue as they looked into the opening sky.

‘Dark have been my dreams of late,’ he said, ‘but I feel as one new-awakened…’

Theoden then speaks of the coming doom. Edoras and Meduseld shall fall, he says, and “fire shall devour the high seat.” But he asks the all-important question.

‘What is to be done?’

‘Much,’ said Gandalf.

I love this sequence. Choose hope or else despair. It’s not about just “looking on the bright side,” or “just don’t give up!” The presence of hope does not remove the threats that Theoden faces. But it does propel him to ask this simple question.

When we ask, on the brink of despair: “what is to be done?” Hope replies: “Much!”

Acting With Hope

What, specifically, ought Theoden to do, though?

From this moment on, we see a divergence between Theoden on-page and Theoden on-screen, a divergence that doesn’t resolve until the King arrives outside Minas Tirith.

In both cases here at Edoras, Theoden immediately asks Gandalf what ought to be done. Gandalf replies (more or less in both cases) with “destroy the threat of Saruman, while we have time.”

One striking and immediate difference between the books and films is Theoden’s attitude toward war. In the books, Theoden never hesitates to act decisively. He agrees with Gandalf, sends the people to mountain shelters, and musters for war. He even demurs to Aragorn’s suggestion to go that same day rather than to show Aragorn and friends the hospitality that would be King Theoden’s duty as host.

There’s none of the weird drama that happens in the movie, where Theoden doesn’t want to face “open war” against the sorcerer who just cursed him, or against the orcs that are murdering his people. Theoden doesn’t distrust Gandalf—who literally just freed him from spiritual enslavement. I say all this despite loving the movies, and thinking that this conflict is generally well-done in the movies, with subtle details and excellent acting.

In the books, Theoden musters his forces and flies out of Edoras to meet them head on.

This is the moral opposite of what Theoden was doing when we met him. Where he was once hiding, now he sallies out. Where he once sat in darkness, now he rides under the sun. Where he invited his enemies into his heart, now he brings force to drive them out.

No longer does Theoden despair. He chooses hope, no matter how slim.

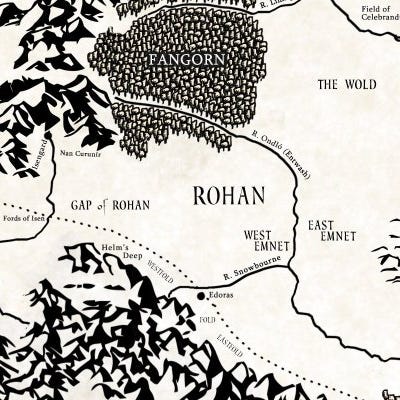

Aside from being brave, Theoden’s decision to ride to war makes strategic sense. The fortress of Isengard is on the far side of the River Isen (the Isen’s Guard), so if an army is attacking from there, then one of the best courses of action is to stop that army at the one place it can cross: the ford. Theoden’s vassal-lords know this too, which is why Erkenbrand, Lord of the Westfold, has by now already mustered his local forces to oppose Saruman’s forces at the Isen.3

It is only later—once Theoden encounters routed elements of Erkenbrand’s army and realizes that the ford has already been lost—that Theoden makes for Helm’s Deep, which is nearby.

This is likewise not the “avoidant” decision that it’s made out to be in the movies. It’s easy to think that running behind a wall is a natural extension of a desire to bury one’s head in the sand, but that’s far from true. Medieval rulers didn’t build castles because they wanted to hide from their enemies, they made castles because castles make it impossible for an invader to continue their conquest as long as their enemies, the defenders, hold the castle. Basically, Saruman’s army cannot venture further into Rohan without first taking Helm’s Deep, since the Rohirrim can sally forth at any time to attack the orcs from behind.

To a modern audience, going to Helm’s Deep feels like retreating. In reality, going to Helm’s Deep is Theoden’s way of forcing his enemy to make some very uncomfortable decisions. It is a sound strategy given that the containing the threat beyond the Isen has already failed.

And Theoden’s choice is ultimately correct, in the event, since the entire enemy host is wiped out in its attempt to storm the fortress (though this is also due to intervention from allies, like Gandalf and the Huorns, as well as Saruman’s own strategic mistakes).4

The Return of the King movie gives us more examples of an avoidant-Theoden clashing with his depiction in the books. Where movie-Theoden hesitates and about whether or not to respond to Gondor’s call for aid, book-Theoden has already mustered the Rohirrim before the call even comes. When the fires of the beacons reach Rohan, Theoden isn’t sitting at Edoras just hoping his problems go away. He’s at Dunharrow, with thousands of riders sharpening their spears, preparing to make all haste to Minas Tirith, to death or victory.

Suffice it to say: Theoden is not the conflict-avoidant old man depicted in the movies. Nor does he constantly need to be told how to act by our more-capable heroes.

Aragorn > Theoden?

Why is Theoden treated this way in the movies? The simple answer is Aragorn.

To best adapt Tolkien’s epic onto the screen, the screenwriters felt the need to give Aragorn a full character arc.

In the books, Aragorn meets the hobbits in the Prancing Pony and tells them, flat-out, “My name is Aragorn and I’m the long-lost King of Gondor and Arnor and I am going to return to Minas Tirith to reestablish the Kingdom. And this right here is the Sword that was Broken. I’m going to Rivendell to re-forge it and then bring it to war against Sauron. Wanna come?” Other examples abound, but basically Aragorn begins and ends the books in the same place personally. He doesn’t change, even if his circumstances and responsibilities do.

That sort of static character may not play very well with a popular movie audience though, especially when Aragorn needs to carry one of the major threads of the story as a protagonist (the main thread being Frodo & Sam, with tertiary threads following Merry and Pippin).

The character arc that the films thus give Aragorn is one of accepting his role as King of Gondor. When we meet him he doesn’t want kingship; he’s fearful of his ability to lead rightly, believing that he will fail like his forefather Isildur.

So Aragorn has to grow in self-confidence as a leader. How? Part of it lies in leading Theoden to do the right things as a King of Men. By introducing Aragorn’s arc, the screenwriters also introduce Theoden as a foil to Aragorn, to accelerate his growth.

In every example I can think of where Theoden is less brave than in the books, the movies always use it to show how awesome Aragorn is.

When Theoden is afraid of ‘open war’ in Rohan, it is Aragorn who flatly tells him “Open war is already upon you.”

When Theoden wants to “hide” at Helm’s Deep (he doesn’t. Helm’s Deep is the sound decision), Aragorn has to remind him that Saruman’s objective is to destroy the people of Rohan.

When Theoden manages the battle from the keep, Aragorn is down in the trenches.

When Theoden gets stabbed at the gate, it is Aragorn who buys him time by leaping to the causeway.

When Theoden is again giving into despair, it is Aragorn who tells him “Ride Out With Me!”

I don’t think it was necessarily wrong for the screenwriters to add this arc and the corresponding drama. Aragorn likely would have been less compelling a character if he had no arc. And overall, I deeply love those movies.

But man, they did my boy Theoden dirty.

‘Forth Eorlingas!’

Why do I love Theoden so much?

I love Theoden because I’ve been the guy in that chair. I’ve been the one to look around and decide that the best course of action is to shutter myself away, literally and figuratively, to let my old and wounded heart beat slower and slower, until there’s hardly a scrap of light left.

I love Theoden because I’ve been in a place where beauty, in some form or another, breaks the clouds just enough for me to think, “It is not so dark here.”

For Theoden, once he breathes that free air, things remain pretty bad for him. It’s not just in his head. Saruman’s host is bearing down on him. His son is dead! Mordor marches against his allies in the South. Things. Are. Bad.

But hope is not an emotion, or a set of circumstances. It is a decision. Choose hope or else despair.

I feel that choice in my bones. Don’t you?

What does Theoden do?

He rides out to face his enemy. And really, at no point in the rest of Theoden’s life does he ever get to see a complete victory. The Battle at Helm’s Deep sees his fears come true: the walls built by his forefathers, Eorl and Brego and Helm Hammerhand, are undone by evil fire. His line is ended with the death of his son. The people or Rohan are expended in the war against Mordor and Isengard.

But Theoden keeps riding out.

When Theoden first re-grasps his sword at Edoras, “he gave a great cry. His voice rang clear as he chanted in the tongue of Rohan's call to arms:

Arise now, arise, Riders of Theoden!

Dire deeds awake, dark is it eastward.

Let horse be bridled, horn be sounded!

Forth Eorlingas!

Is there hope to be found against the reckless hate of Mordor? Perhaps Theoden himself cannot see it. But he acts out of hope.

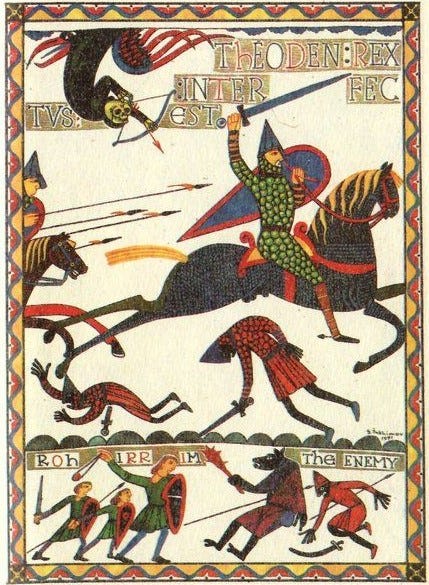

In The Return of the King, when Theoden sees the great host of Mordor splayed out on the Pelennor Fields, his heart nearly despairs. But hope is then stirred by the visceral advance of evil before him, and he reprises his earlier call to arms:

…the king sat upon Snowmane, motionless, gazing upon the agony of Minas Tirith, as if stricken suddenly by anguish, or by dread. He seemed to shrink down, cowed by age. [...] as darkness closed again there came rolling over the fields a great boom.

At that sound the bent shape of the king sprang suddenly erect. Tall and proud he seemed again; and rising in his stirrups he cried in a loud voice, more clear than any there had ever heard a mortal achieve before:

Arise, arise, Riders of Theoden!

Fell deeds awake: fire and slaughter!

spear shall be shaken, shield be splintered,

a sword-day, a red day, ere the sun rises!

Ride now, ride now! Ride to Gondor!

Ride now, ride now! Ride to Gondor!

At Minas Tirith, Theoden and his riders cannot see a way to victory. Doom awaits them, and even their glory will be anonymous because no one will be left to remember them. And yet they go out and fight anyway! They act with hope even when they feel none.

Hope, like love, is a choice. It is not a calculation of reason. It is not an emotion that we should do our best to hold on to. It is a choice. And it is worth choosing.

That’s why Theoden’s speech in The Return of the King is so stirring. It is an act of pure hope and sacrifice.

He and his riders do what is right—refusing to let evil win unopposed—no matter the cost. Death? Ruin? Earthly anonymity?

“No matter!” says Theoden, with his actions. “I will ride to the world’s ending, so that in the company of our fathers we will not be ashamed.”

And Tolkien does something brilliant in that Theoden doesn’t live long enough to see the books’ happy ending. He dies in the field without seeing victory. He doesn't get to see Sauron defeated. In the books, at least, he dies when the battle is still very much in the balance, and his final breath is spent proclaiming Eomer as the new King of Rohan. He dies before Merry can tell him that it was his beloved niece Eowyn who avenged him. There is so much that we the readers can point to as a way to show that Theoden’s hope was worth it, and was “correct,” in the end.

Yet Theoden the character cannot see many of those things. Theoden's own story seems incomplete.

And yet some of Theoden’s final words, given to Merry Brandybuck, read:

My body is broken. I go now to my fathers. And even in their mighty company I shall not now be ashamed. I felled the black serpent. A grim morn, and a glad day, and a golden sunset.

That's the final lesson here: hope dies when we focus on ourselves, but it finds life through loving others and working for their good instead of our own. Theoden sat in his dark hall because he feared for his own peace and safety, but he rode out to the Pelennor because he had hope for others'.

And that hope is made “worthwhile” not because its proven to be right or wrong about certain circumstances, but because it focuses us on what is most important: love and self-sacrifice.

The fire of hope does not magically solve our problems; but it does enable heroism within us, even if heroes don’t always make it back home.

That’s why I love Theoden. He lives in a place of hopelessness that we can so often—and so easily—find ourselves. And he shows us the way out: courageous self-sacrifice, chosen in hope.

I’ll wrap it up there.

Forth now, my friends, and fear no darkness!

✹ ✹ ✹

If you like what you’ve read here and want me to keep making stuff like this, you can help me do that by liking, commenting, or sharing this piece. You can also see all my writing by visiting this page.

✹ ✹ ✹

✹ ✹ ✹

Maybe. It’s hard to say ‘favorite character’ when Samwise Gamgee also exists.

Co-written by Phillipa Boyens and Fran Walsh. Boyens in particular ought to get more praise for these movies, as she also translated a whole lot of Tolkien’s elvish, and wrote Elvish lyrics for the Howard Shore’s amazing soundtrack.

The extended films hint at this fight at the ford, with Theodred’s defeat happening there, and Eomer recovering his mostly-dead body.

If you want a fuller treatment of the Saruman’s Rohan Campaign from a military-historical perspective, check out historian Brett Devereaux’s excellent and thorough treatment of the topic.

It’s been a few years since I read the book so I needed the refresher on Theoden’s character! The true Theoden is a much needed inspiration for us to look to in these days, as is the case with many of Tolkien’s characters.

Wonderful essay, sir. You give a very insightful look at Théoden and do a fine job at pointing to how some of the differences between the books and films don't work so well, and I say this as someone who does enjoy both portrayals of the character.

That being the case, there is an important difference between the book and film versions of Théoden which I'd like to note- his age. The books make it expressly clear that Théoden is still very much an elderly man when he rises back to his feet and starts to feel the light of hope again. Unlike in the movie, his body doesn't change to match this reawakening. He simply stands up straighter, casts his cane aside, and takes up his sword once more.

In the films he is visibly a much younger man once Saruman's influence is pushed out of him. Not a young man by any means, but also not the same wizened ruler that he is in the books. As you say, part of this is because Aragorn's character needs a proper arc in the movies, since he doesn't have one in the books. Sometimes this grates against Théoden's character as we knew him, but I don't think that means Théoden was necessarily done dirty here. (Not always, anyway.) I personally like his arc within the films almost as much as I do his arc in the books, because it allows us to more actively see a man pulling himself from despair to become the leader he needs to be. Now I'd probably feel differently if the films actually did lean hard on the idea that his decisions are made out of cowardice, but though Aragorn and Gandalf do argue this, the films also actively show that no, Théoden isn't making his choices out of a sense of fear. He's making his choices out of concern for the wellbeing of his people, to the point that he journeys to Helm's Deep right alongside them. It's a portrayal that's not so ungracious as it may first seem.