Two Simple Questions That Will Give Depth to Your Characters

Getting beyond “What do they want and why?”

There are roughly three billion guides about how to create or deepen a character for your story, and most of them are garbage.

Maybe that’s harsh, but I stand by it.

These garbage guides come in a few varieties. Maybe you’ve seen these in the wild…

“Answer these Surface Level Questions!” What’s their name? What do they look like? What culture do they come from?

These guides are so superficial that if you need it this early in the process then you probably don’t have the creative hutzpa to be a writer. Plus, they’re full of useless questions. No, I don’t need to know if my character had a beloved pet when they were a child, thanks very much.

“Answer these 300 questions to determine which of these 18 personalities your character has! Get ready to learn all 18!”

If I could spend 40 minutes confidently answering questions about every conceivable situation my character could be in, then I wouldn’t need a guide, would I?

“Answer these multiple choice questions that leave zero room for nuance!”

Ask bland, uninteresting questions? Get bland, uninteresting character advice.

Then there’s one actually useful type of character-question-guide, which takes into account story structure, and usually comes from bona-fide authors. It’ll have prompts like:

Give every character a desire.

Make sure you understand your character’s goals and motivations.

Determine a few core values—ideas of morality or their worldview—that will inform their decisions.

How will the character change, if at all? What, if anything, will force them to change?

Those are all really important, but chances are if you already have a story and you already have a character or three, then you also have a sense of what they want, how they view the world, and what sort of arc you want for them.

I want to give you something deeper, something that can help on the scene-level, to make your characters memorable, realistic, and distinct from one another.

So this is a character quiz, but there are only two questions, and both are binary, meaning that they have only A-or-B answers.

It’s easy enough to find the answers if you already have a sense of a character’s personality, but it can help guide you as you fill in the cracks and put that character down in prose. If you don’t know yet, decide on whim or flip a coin.

AND you can do this whether you’re a discovery writer or an outliner, (or both/neither), and regardless of whether or not you have an outline.

Enough intro. Let’s get to it.

The Two Questions

Both questions are about how your character reacts to things on an internal, emotional level. It’s not about the character’s deliberate actions.

Question 1:

On an emotional level, does the character react quickly or slowly?

Example:

A waiter is rude to you. Quickly might look like you getting angry and upset while they’re still at your table. Slowly might look like you realizing how it made you feel only later, once you’re waiting for your food.

Question 2:

On an emotional level, does the character react strongly or weakly?

Example:

Weakly means the rude waiter doesn’t totally ruin your meal because it wasn’t that big a deal, after all. Strongly means you get riled up about it, whether in the moment (quick) or as you stewed about it on the car-ride home (slow)

That’s it. Those are the only questions.

Before we go further: no answer is better than any other.

For instance, “weak” emotional reactions are not in any way a bad thing! If a hero looks at the dragon and sees that it’s bigger than he thought, and then thinks “oh well. Time to fight,” then that’s actually a “weak” emotional reaction, making light or danger and refusing to take everything super seriously.

You know that guy who takes touch-football way too seriously at the family reunion? That’s a guy who can’t ever have a “weak” reaction to things, even when he should. Weak reaction =/= weak person.

The same goes for “slow” reactions. It might sound bad but it absolutely is not. “Slow” reactions just mean the character takes time to process things. Ever seen someone who’s just entirely unflappable? No matter what happens or what goes wrong, they can just keep moving forward? Sometimes, that’s what a ‘slow’ reaction can look like: calm, cool, collected.

So just get in your head now: quick, slow, strong, weak… these are neutral terms.

So How Do These Work?

Okay, you answered the questions. Now what? How do you use this?

These two questions together inform a person’s “temperament,” with four possible answers.

Temperament isn’t the same as personality, but we are venturing into the space of “personality tests.” I know, I know. Bear with me.

I’ve heard of people doing personality tests for their characters as a way to better flesh them out; but most tests are either so broad as to be useless or so exhaustive that you could only finish it if you already have a very clear and complete idea of your character (in which case, you don’t need the test).

But with temperaments, There are only four possibilities. And while that might seem simplistic—well, it is simplistic—temperament isn’t meant to be a barometer for a person’s whole personality.

It’s just a way to understand how a person (or character) responds to new information and events regardless if the stimulus is good or bad.

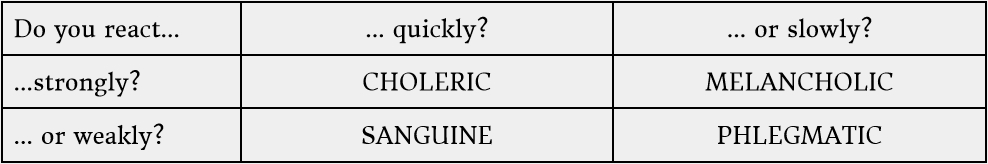

So: you have your two answers. Here’s the breakdown:

Every person theoretically has both a primary and secondary temperament. You may find yourself identifying with more than one as we go. The corners of this box are opposites, by the way, and opposite temperaments generally don’t manifest in the same person. That’s not a rule though! Every combination is possible.

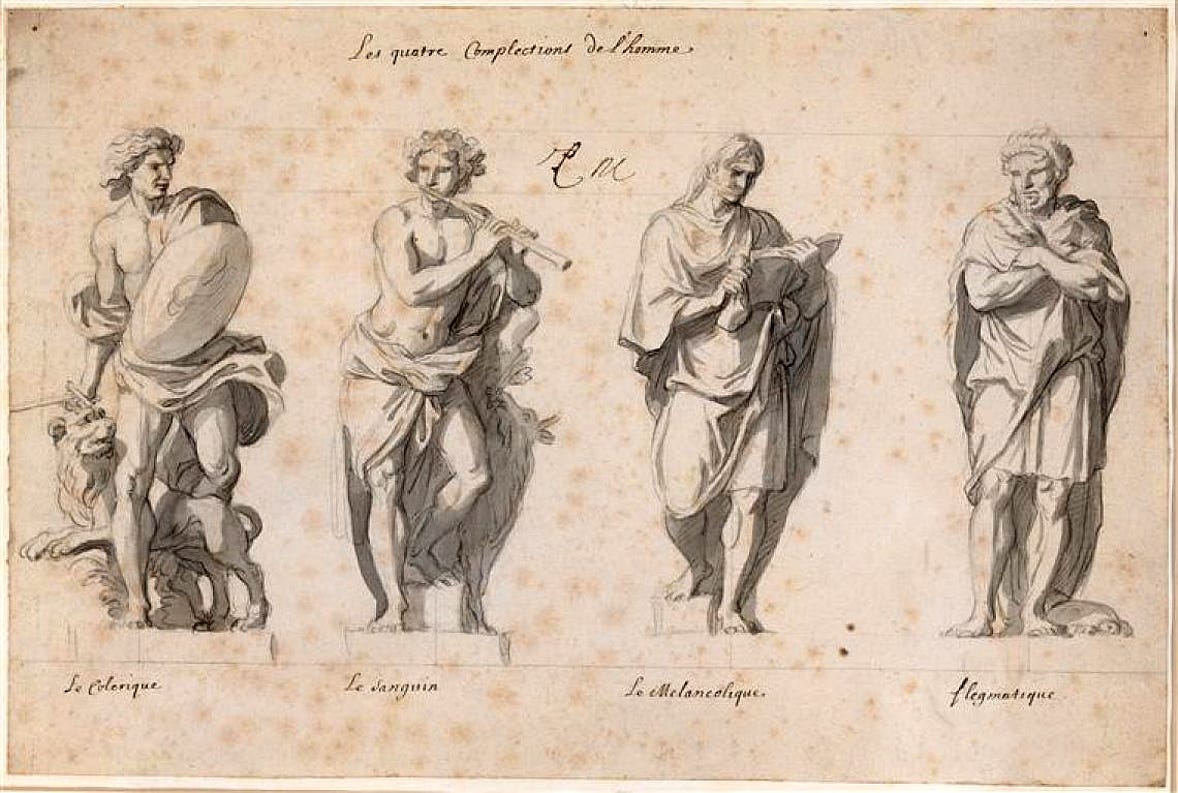

The Temperaments Explained

For each temperament, we’re gonna explain what kinds of emotional reactions (and corresponding possible actions) each temperament generally has.

A character’s (or a real-life person’s) temperament might make them susceptible to certain character flaws, but simultaneously make it easier for them to have particular strengths and more heroic traits. So we’ll look at what each temperament might look like in a controlled, well-adjusted person (we’ll call this virtue, a la Aristotle) and also what that temperament might look like in a less-controlled, more selfish person (we’ll call this vice).

Let’s move through the four, and we’ll keep using the rude waiter as an example.

Quick and Strong: The Choleric

Cholerics react immediately to things and they do so with strength. Cholerics know what they feel, know what they want, and so they often go right at it. They are generally sure of themselves, decisive, and willing to work hard.

With virtue, cholerics can become natural leaders, dependable, work- and goal-oriented, organized, and confident.

With vice, they can be bossy, arrogant, unwilling to listen, perfectionist, and can make snap judgements from which they do not budge. Honestly, cholerics sometimes get a bad rap, but the world needs them.

To use a stereotype, the choleric is “Type A” sort of person.

Of the four temperaments, the choleric is most likely to confront the rude waiter, then and there, or call a manager.

A choleric hero is a decisive one, jumping into action at a moment’s notice. A choleric villain is the kind that loses his absolute mind and starts killing minions when he hears that the good guys escaped.

Quick and Weak: The Sanguine

Sanguines have quick emotional reactions which fade rather quickly. They may experience a wide range of emotions in a given day, but still not lose a wink of sleep at night. They generally live very much in the moment. The ‘here now, gone soon’ nature of their emotions can lead them to seek out variety, novelty, and adventure.

With virtue, sanguines find it easy to be affable, empathetic, and genuine.

With vice, they can be flighty, vain, unreliable, or easily distracted.

Their surface-level stereotype is “The People Person,” or “The Extrovert.”

The sanguine may get upset by the waiter, but it’s maybe not a big deal. And they’ll return to a great mood when the french fries hit the table.

A sanguine hero might be a lovable rogue or a quick-witted team leader. Avatar Aang comes to mind. A sanguine villain might look like a schmoozing, corrupt politician or a chaotic evil, “I’m in this for the kicks” sort of sadist.

Slow and Strong: Melancholic

Melancholics feel emotions very deeply, but need time to process. They have Opinions, they just might not know what those are yet. They tend to be introspective, patient, intellectual, romantic or idealist, and filled with angst.

With virtue, they are self-sacrificial, wise, humble, and hopeful.

With vice, they are pessimistic, depression-prone, cynical, bitter, full of self-doubt, over-thinkers, and (like their strong-feeling comrades the cholerics) perfectionist. The melancholic is the most accurately named of the four temperaments.

The surface-level stereotype is “The Introvert” or “Tortured Artist”

The melancholic will start arguing with the imaginary waiter on the car ride home, not realizing just how much it bothered them until much later.

The melancholic hero probably broods, but comes to have very powerful emotional arcs (like the clinically-depressed Kaladin from Stormlight Archives). Frankly, the melancholic villain probably also broods, but then does bad stuff with all that pent-up emotion. Baron von Harkonnen comes to mind, but who can tell with him? I’d classify Zuko from Avatar: The Last Airbender as a melancholic.

Slow and Weak: Phlegmatic

Okay okay, that sounds bad, right? Wrong. Remember: neutral terms.

The Phlegmatic has weaker emotional reactions and does not react rapidly. This often becomes a “go-with-the-flow” attitude. Phlegmatics are not easily surprised or amazed, nor easily angered. They are up for anything, but generally won’t be the one to organize something.

In virtue, they can be patient, non-judgmental, kind, willing to listen, friendly, quick to love, quick to forgive, and easy to like.

In vice, they can become lazy, easily misled, flaky, and apathetic.

The surface-level stereotype is “Type B” or “the Whatever Dude”

The phlegmatic was probably never bothered by the waiter in the first place.

A phlegmatic probably isn’t the protagonist, but can still be a great character, like Mat Cauthon of Wheel of Time or Peregrine Took from Lord of the Rings; a lovable chap who got swept up in something pretty big, and who will want to see out the adventure, even if they also really just want to go home. A phlegmatic villain is the kind that is never dissuaded, never phased, never shows emotion.

Final Caveat

Again, these are just ways to describe emotional reactions. They do not describe a full personality, and they definitely do not describe the kinds of actions a person takes. These reactions can tend towards certain actions (as in the examples above), but temperaments are far from prescriptive and far from binding. Cholerics can be patient like phlegmatic opposites. A sanguine person can get sad like a melancholic because they’re both just people. This isn’t meant to pigeon-hole your characters! It’s just another way to draw them out onto the page and contrast them.

Putting This Into Your Writing

There’s a bunch of ways that fiddling around with temperaments can help your characters come to life. Here’s five.

1. It can help you get to know them.

Temperaments can be most useful when you already have a solid idea about a character, but you need to zoom in a bit and get to know them in the small moments.

Knowing their major motivations, their values, and the obstacles they’re going to overcome are all vital, but none of those automatically give you a sense of their mood in a scene, or a clarity on how articulate they might be, or how readily they will share their mind. Yet those are the things that drive dialogue, or dictate how they process the big events that are sure to happen in the plot.

I myself have found this a useful exercise when during the stage of writing when I take an outline and begin turning it into prose. Because…

2. It can guide scene creation

If two characters are going to have a verbal confrontation: are they both likely to engage, and for how long? Will they keep fighting until they resolve things (like a choleric or a sanguine), or is someone (a melancholic, for instance) going to get flustered and walk away to collect their thoughts? After the fight, how long before one or the other tries to reconcile? A choleric or melancholic might stew for a long time or require more effort to get back to equilibrium, whereas a sanguine or phlegmatic might bounce back quickly and bury the hatchet.

None of these differences really change the plot! Characters fight → characters get their thoughts and emotions out → Characters reconcile.

Nonetheless, temperaments change the story on a small scale. Will the fight be long or short? Will it be one scene or two? Do you need to spend time following one character as they sit in the dark and chew on the hurtful things that were said?

Temperament can help you with all of that, regardless of motivations, desires, values, goals, and relationships.

3. It can help add natural emotional beats

Temperament can also go a long way to help you pace out a longer story: a ‘slow’ reactor (a melancholic or a phlegmatic) will need time to process the various things that have happened to them, which make for great reset/sequel scenes after the main action takes place. These are the kinds of ensemble scenes where we really get to know the characters because they’re bonding and processing the plot together, like Luke aboard the Millennium Falcon in A New Hope, or the Fellowship mourning Gandalf in Lothlorien. Because we have some more melancholic characters (Luke, maybe, but certainly Frodo and Aragorn), these scenes are vital to the audience's connection to the characters, and things would feel rushed without them.

4. It can differente characters from each other (& from you)

Are all your characters starting to sound the same? Give them different temperaments. Give only some of them the ability to quickly process their own emotions. Give only some of them the ability to brush things off. Give only some of them deep, heavy feelings.

Even better: consider your own temperament. Writers often slip into making all their characters like themselves. By thinking of temperament, you can have a guide to creating a character entirely unlike yourself, without tons of legwork. Make that character zig when you would zag.

5. It can add flesh to the cardboard

Most books have characters that I call “cardboard cutouts.” The characters that might have names, but they’re just Imperial Guard Number Seven or Frightened Inmate Number Two. You don’t need a character sheet for them, but if you flip a coin twice and pick a temperament, you can add a layer of realistic depth that will stand up a lot better than the cardboard cutout you first needed, because that temperament might show up even in the tiny bits of dialogue and the minuscule moments that character is on-page.

What Do You Think?

I’ll leave it there. As always, I’m sharing this because it’s helped me with my own writing, and I hope it can help you.

Let me know what you think.

(Sorry I wrote a long post. I didn’t have time to write a short one.)

✹ ✹ ✹

If you like what you’ve read here and want me to keep making stuff like this, you can help me do that by liking, commenting, or sharing this piece. You can also see all my writing by visiting this page.

✹ ✹ ✹

✹ ✹ ✹

This is great - thanks for sharing it! Definitely some food for thought, and it’ll likely become my go-to character personality paradigm. (And nice Twain nod at the end!)