In one of my recent posts I explained how my twin loves of medieval history and fantasy fiction are intrinsically connected, at least within my own heart and imagination.

Today I want to expand on that theme a bit, and explore how historical narratives have shaped me as a reader, worldbuilder, and storyteller. I’ll share some of the principles and guide-posts I use from the study of history in my writing in the hope that you too can draw from the wellspring of history in your own works; it’s a toolbox, and I want to share it with you.

And—why not be fully transparent with you, my valued readers?—I expect that doing this will give any potential fans a sense of the kinds of stories I aspire to write and hopefully draw them in! (and, for further transparency, this is something I can write about quickly enough during a week where I’ve had no time to write or prepare something more substantive for you).1

That Dragon-World Better Be Realistic!

Any narrative—on page, screen, or stage—depends upon the suspension of disbelief. Even for non-fiction, an audience will intuitively allow certain “unrealities” in the unfolding of the narrative, some of which might be inherent in the medium (we can’t physically see the events described in non-fiction books, even if we recognize they really happened). This conversation could get very meta so I’m just going to steer away now.

Narrative needs suspension of disbelief.

Put another way, a story succeeds insofar as it “immerses” us in the narrative. We see this sort of language all the time. Good stories “transport” us away; a good story is one you can “enter into,” whereas bad writing “kicks us out” of the story, or makes the “hand of the author” visible.

This is especially true of fantasy fiction, where the setting uses unreal things as a feature rather than a bug. The immersion and escapism is the primary mechanism for whatever it is the author’s doing. The unreal somehow reveals that which is real. Once again we’re nearing deep meta-narrative stuff better left for another time. So again I’ll steer away.

All of this puts spec-fic writers in a weird place where we need to make a setting (and characters within it) that feels real and tangible, while simultaneously packing it with things that are inherently irrational and non-existent, like dragons and goblins and magical artifacts and sentient mushrooms.

It works because ultimately, readers don’t actually care about whether a world or setting is “realistic.” What they care about is actually internal consistency. A setting can be as limitlessly unrealistic as long as it is presented as a place with rules and boundaries. If those rules and boundaries are broken, then it will shatter the audience’s suspension of disbelief, destroying their immersion and alienating them from the story.

This is why the same audience that had no problem being immersed in the inherent unreality of a talking tree carrying two hobbits later had a very hard time accepting the idea of a she-elf and a dwarf making eyes at each other.

The fact that one seems normal and the other could be immersion-breaking is a perfect encapsulation of what it means for a fantasy world to be “realistic” or not. It’s not about realism. It’s about internal consistency.

History as a Ruleset for Realism

All things being equal, the baseline expectation of rules and boundaries for a given setting are basically just “the real world.” We expect any fictional world to work like our own world, until the author tells us differently.

One of the things we carry into fictional work is our ideas about human nature. When we see people running around Westeros or Arrakis or Osten Ard, we assume they will behave with the same general nature as humans in our own world. Just as we assume gravity will still happen, we assume these people will need food and water and sleep and they’ll do predictably human things like work and love and fight and form societies…

And this is where history comes in.

The study of history is principally about human behavior. It’s the story of how individuals and groups interact with each other, the ways cultures develop, and the ways we interact with the world we inhabit.

These are the bones of any well-built fictional world. Just as a talented musician can take a melody and improvise upon it, just as a good architect can take a structural form and develop it into something more beautiful, just as a painter can take the outline of a person’s visage and draw out a deeper aesthetic, so too does a fantasy author take our expectations and biases about human behaviors and mold them into a rich and fantastic setting for a story.

History becomes the ruleset, the basic and unnoticed boundaries of the world. The better an author’s understanding of that ruleset, the greater their freedom to use it, expand it, change it, and use it to its fullest extent.

With a proper understanding of real-world historical settings, an author can more easily create engaging, immersive, real-feeling fantastical settings.

But with only a shallow understanding of real-world historical settings, an author might end up creating a shallow caricature of human society. With a bad base, the additions of the unreal—the dragons and potion shops—will appear shaky, arbitrary, and similarly shallow. More on this later.

History as Fodder for the Fantastical

Using true historical understanding as the “base” for a fantasy setting has the added benefit of being completely foreign to modern readers even while being absolutely true and real.

It’s often said that “the past is a foreign country.” When you really dig into it, real human societies can seem more strange than the most fantastical myths.

For instance, depending on the historical “setting,” you get weird things:

The native tongue of the Kings of England was French from 1066 to ~1400 (so for longer than the United States has existed).

One way to climb the social ladder might be to have your balls chopped off.

Sports teams’ rivalries could get so heated that they could lead to riots capable of toppling imperial dynasties.

The Uffington White Horse totally isn’t fake. And neither is the giant chalk outline of a naked giant. In fact, the Nazca Lines mean this sort of thing is actually kinda normal.

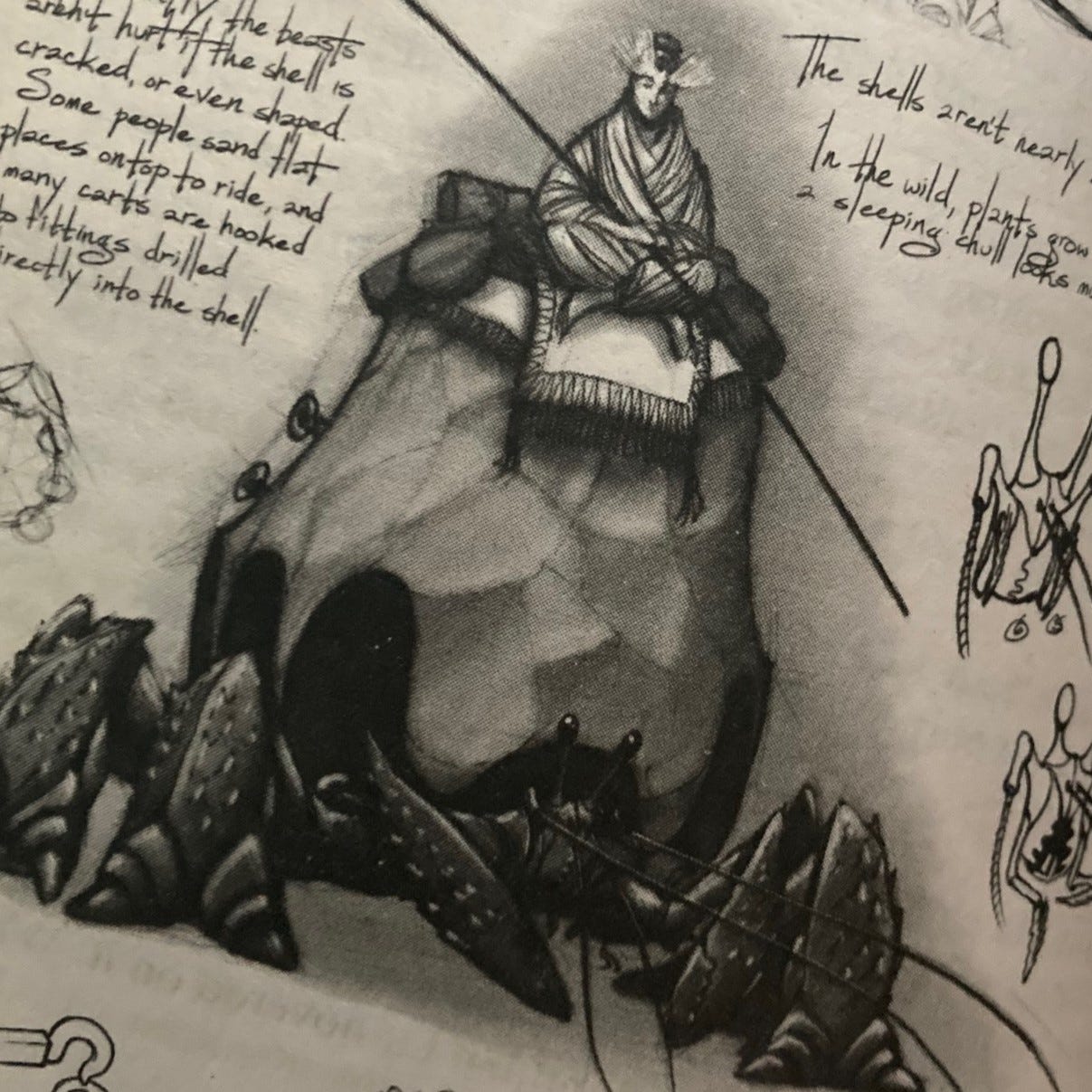

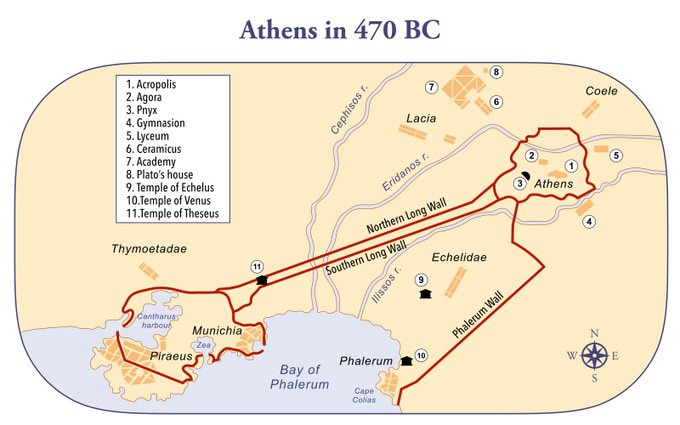

Sometimes city walls actually looked like this:

If an author/worldbuilder leans into some of those foreign bits, it can create a narrative world that immediately strikes that balance of real-but-unreal. It will feel unreal and fantastical because it is wholly different from how our world operates, but it will feel real because it is already aligned with human nature (because humans already did it).

Scattered Thoughts & Caveats

Now I know what I’m describing could just be called “historical fantasy,” a subgenre where fantastical elements are incorporated into a work that is otherwise historical fiction. One example might be Robert Egger’s 2022 film, The Northman. It’s literally Iceland with literal vikings, but also Scandinavian folk magic actually works.

“Historical fantasy” could also include things that are fully secondary worlds but so closely resemble real events that the line between this world and the secondary world is a bit blurred (some of Guy Gavriel Kay’s novels might fit this classification, given that his settings are usually and unabashedly mirrors of real-world settings).

But what I’m arguing for here is something more broad; a fantasy author need not become a magic-writing historical fiction writer in order to be good at fantasy. Remember: the dynamics present in historical events are the result of human nature and the patterns we organically create in this world. When the audience sees people in your world, they will automatically assume they behave like people in this world. As a result, using the small- and large-scale dynamics of human history for your fake world can be a powerful tool for maintaining internal consistency and the suspension of disbelief.

Principles For Historio-fantastical Worldbuilding

I want to keep expanding on this idea, and I will in later posts, but frankly I’m running out of time for today. In the interest of getting this to your inbox in a timely fashion, I’m going to close out with a few of those promised “guide-posts” and “guardrails” for historio-fantastical2 settings.

Then in the future, I can unpack some specific examples and show how I used them to create my world. Let’s begin:

The People In the Past Were Not Stupid

Do not assume that you know better than people of the past (though sometimes, you do know better). If there was a particular way of doing things that seems dumb to you, figure out why people in the past did it that way before you write a story where such a thing matters.

I happen to think that hereditary aristocracy is a dumb system of government. But gosh darn’it it’s a lot of fun to write, and I’m fascinated by the ways that interpersonal and familial relationships can have drastic consequences for things like national security. If I went and wrote in a setting where I don’t understand why such a government exists, or why lots of people would support it, or why huge swathes of humanity would view an inbred child as a legitimate ruler and then go and fight on his behalf … well then the story would probably read like meaningless grimdark or a shallow vomiting of the author’s political philosophy.3

You know what that wouldn’t be? An interesting story.

Cultures Are Neither Monolithic nor Rigidly Exclusionary

This is the “planet of hats” problem4, which can be solved by becoming more immersed in history. Yes, every culture has its unique features and its worth exploring those unique features to their logical conclusions. But it’s a mistake to take one particular unique feature of a culture or nation and then make it their entire identity, especially when that feature is just aesthetic.

Wheel of Time has a special place in my heart, but boy are there a lot of hat-planets. The Illianers wear beards but no mustaches. Every helmet of every Carheiner is the same shape. Every woman in the nation wears a dress like this but as soon as you cross the river over there to that nation they all wear dresses like that.

Real cultures change, share, borrow, and morph. Fashions come and go. And identity is a deep and quasi-mysterious thing. Sure, the King of England primarily spoke French in 1337 but you better believe he and the rest of his knights absolutely did not think of themselves as French, and neither did their subjects.

People Generally Believed In What They Said They Believed In

If you put any kind of religion into your world, then remember that people should actually believe in that religion. Because if they don’t believe it, the religion wouldn’t exist. Religion can take a total backseat to whatever else you want the story to be about, or it can be totally absent. But if you do include it, make people actually believe in it.

The fact is, temples, shrines, sanctuaries… these things only get built if people actually believe in the claims that the religious class is making. A priestly class isn’t going to become at all powerful if everyone actually thinks they’re full of crap. A priestess can’t get the resources to build a Temple to Divine Whatsherface if people think the goddess is a social construct.

If (totally spitballing here) there was enough time and money and support to build a giant temple (oh I don’t know let’s call it a “sept”) to seven divine beings, then chances are that if a ruler burns that temple to the ground then there would be something resembling consequences for their actions.

Conflicts Are More Complex Than Hatred or Greed

Hatred absolutely exists in the real world and it can be a powerful imaginative tool within a fantasy setting, but the kind of hatred that brings about true, intractable conflict takes a very, very long time to develop. The vast majority of human conflicts are instead a competition over resources. Even ideological conflicts like World War II or the American Civil War can be more fully understood (but never completely understood) by looking at material realities.

However, human societies always seek some level of moral justification for their conflicts. Sometimes this can be a cover, but a fair number of people have to believe their side is morally right or else they just walk away. Usually a conflict is more complex than just “I want your stuff.”

Territorial disputes, diplomatic hostilities, religious differences, rivalries over competing legitimizing myths5—these things mattered in historical conflicts, and they provide ample inspiration for fantasy-setting conflicts as well. Sure, you could have a bunch of nobles who are all just greedy and want the throne (like some kind of game… over some thrones… or something), but without evaluating that any more deeply the hordes of people in their armies might just seem like set-dressing. Rather than, you know, like people.

Conclusion

I said I was running out of time, and I absolutely am. Assuming you all don’t talk me out of it (by all means, tell me if this was useless), I’ll probably keep exploring this topic in the future.

✹ ✹ ✹

UPDATE: I did keep exploring this topic. Check it out:

✹ ✹ ✹

If you like what you’ve read here and want me to keep making stuff like this, you can help me do that by liking, commenting, or sharing this piece. You can also see all my writing by visiting this page.

There will be typos and this is why.

This is a word now.

“Hurr durr everyone in my world is a dumb peasant hurrdy durr I’m so enlightened”

Named because of Star Trek planets where the only real distinguishing feature of a given planet are the unique hats they wear.

“We’re the heirs to Rome!” “No, we’re the heirs to Rome!”

Great essay, and I haven’t quite finished, but I do see one problem. I have noticed that there are certain things that are so ingrained in modern people that even though they were absolutely not true in history, modern people have a very hard time realising that. They are so entrained in their own current mindset that they don’t see it when a book that is theoretically historical is very unreal in a given area.

Loved the essay, Eric. Just some thoughts this brought to mind…

I think people overestimate how much we understand history. Our understanding is warped by propaganda and cultural misconceptions over and over again, adding endless layers of falsities.

Our history books are already anachronistic fantasies, really. To me, playing with those gaps in attested knowledge and the many layers of falsities is what makes historical fantasy so fun.

I love writing mythohistorical Iranian fiction because of historical inaccuracies, not in spite of them. Coming to a crossroads in which I have to choose to lean into or away from a historical misconception, or a western falsehood, or a trope that’s gotten away from itself, etc. is one of my favorite parts of the process!