The Heart of Fantasy According to Tolkien

Pt. 1 on Tolkien's "On Fairy-Stories," with Clifford Stumme: Exploring Faërie, Fantasy, and Myth.

Starting this week and running through the end of October, I’ve teamed up with Clifford Stumme of Past the Dragon to bring you a four-part exploration of J.R.R. Tolkien’s illuminating essay, “On Fairy-Stories.” This is part one, on Tolkien’s idea of Fantasy. Next week, you’ll hear from Clifford about Recovery, then we’ll move to Escape and Consolation, as defined by Tolkien.

In this series, Clifford and I invite you to engage with Tolkien’s thought directly. We’ll walk you through Tolkien’s essay, offering a guided tour of its themes. We certainly hope you will chime in yourselves with comments, correctives, and even essays of your own. Please, engage with Tolkien’s work, engage with ours, engage with each other’s. (At the end of the month, we’ll share a round-up of the most interesting commentary, whatever form it comes in. Be on the lookout!)

Why “On Fairy-Stories” Matters

“On Fairy-Stories” is one of the seminal works of analysis for the fantasy genre. Originally given in 1939 as a lecture among friends and colleagues, the lecture was later expanded and put into print in late 1947.

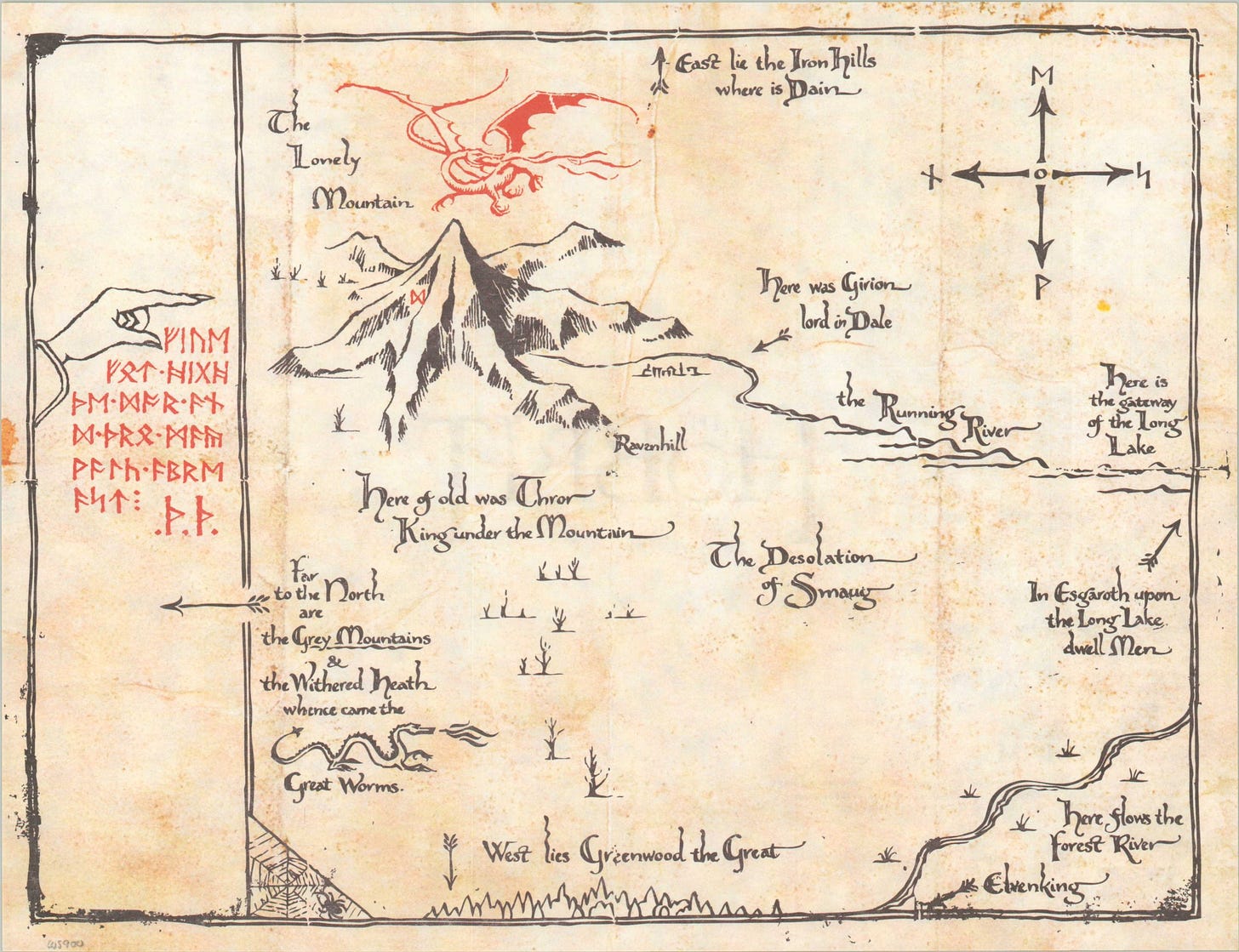

“On Fairy-Stories” is, of course, Tolkien’s explanation of his own craft; Tolkien delivered it not long after the publication of The Hobbit (1937), and put it to paper simultaneous with his work on The Lord of the Rings. For that reason alone the essay is an object of interest to anyone who wants to unpack the worldview of Middle-Earth. The ideas within “On Fairy-Stories” are far more important, however, than a behind-the-scenes memento for fans.

Given that Tolkien’s work was so central to creating and shaping the fantasy genre as we understand it today, it is impossible to fully understand the genre without engaging with Tolkien’s thoughts.

J.R.R. Tolkien is not the last word on the fantastical, nor is he the genre’s singular origin. We must not treat him as such, nor should we treat “On Fairy-Stories” as a hermetically-sealed rulebook which must define the genre for all time.

Nonetheless, because “On Fairy-Stories” is the summation of Tolkien’s thought on the art and craft of fantasy, and because of the importance of Tolkien’s subsequent fiction, we can confidently say that “On Fairy-Stories” provides the philosophical groundwork for what we call modern fantasy literature. And I, for one, am not complaining about that at all.

Let’s get right to it, shall we?

Fairy, Faërie, and Fantasy

Tolkien’s main argument of “On Fairy-Stories” is that the fairy-stories ought not be “relegated to the nursery” as they so often are, but rather that fairy-stories are one of the highest and most rewarding forms of Art possible.1

As with any scholar laying out a case, Tolkien began by defining his terms. We must do the same, especially because the parlance surrounding the fantasy genre has shifted quite significantly in the eight decades since Tolkien first gave his lecture.

Tolkien expands the definition of fairy-story beyond fanciful children’s tales. He says that fairy-stories are not actually about fairies or other fantastical things. Instead, the essence of fairy-stories lies in Fairy—or Faërie—itself, and Faërie is “the realm or state” in which these fantastical things can and do occur. Tolkien writes:

Faërie contains many things besides elves and fays, and besides dwarfs, witches, trolls, giants, or dragons: it holds the seas, the sun, the moon, the sky; and the earth, and all things that are in it: tree and bird, water and stone, wine and bread, and ourselves, mortal men, when we are enchanted. (p. 113)

The presence of these realistic things—the sun, the moon, etc.—in the land of Faërie is worth noting, and they’ll prove to be quite important to Tolkien’s argument. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s stay on definitions for a moment longer.

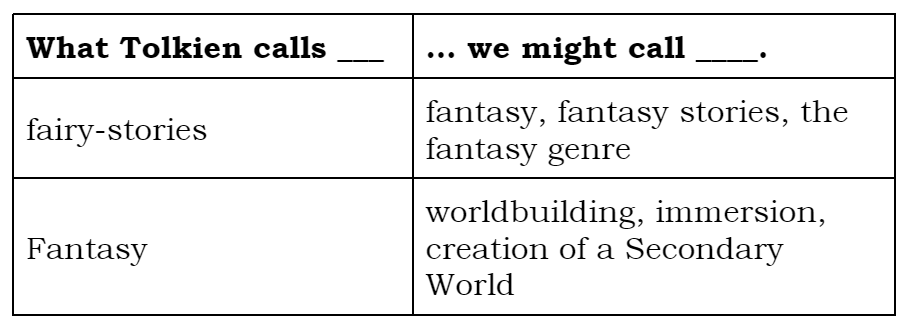

Faërie is the magical otherworld; its presence makes a story a fairy-story. The lack of Faërie means that the literature is something else. In our modern phraseology, we can roughly equate Tolkien’s use of the term “fairy-stories” with our use of the term “fantasy stories” or even just “fantasy.”

We must remember that the fantasy genre as we know it today did not exist under that name while Tolkien was writing “On Fairy-Stories”. I want you to make note of that, because we’re about to follow Tolkien into a long discussion of the term “Fantasy,” by which Tolkien does not mean a genre.

Instead, we could equate Tolkien’s use of Fantasy with a modern usage of “worldbuilding.” I hesitate in that, though, as I find it too reductive. The term “worldbuilding” tends to have a very clinical, engineering quality, with a connotation of technical precision. Meanwhile Tolkien, for reasons we’ll soon see, believes Fantasy to be an art that is primordial, strange, and downright mystic.

But we must move forward, so “worldbuilding” can be our at-hand synonym for Tolkien’s term. As you read this series, remember:

Creating the World of Faërie

If Faërie is the essence of a fairy-story, Fantasy is the craft which constructs and convey’s Faërie to the audience. For Tolkien, Fantasy is an act of imaginative creation which strives to have both the “inner consistency of reality” and the strangeness Faërie, in order to explore reality in some deeper way (pp.138-139). It is the creation of that Secondary World into which we, the audience, can enter.

How does an author accomplish Fantasy, according to Tolkien?

To achieve Fantasy, one must create the world of Faërie within one’s story, whatever precise flavor of Faërie that might be. This is an Art that Tolkien unsurprisingly takes very seriously. He labels it as “sub-creation” of a “Secondary World,” a creation within and beneath our Primary World.2

Conventional wisdom would say that a ‘good’ Secondary World relies on the suspension of disbelief, but Tolkien actually disagrees. Or, at least to him, that would be a failure of literary ambition.

[Willing suspension of disbelief] does not seem to me a good description of what happens [in fairy-stories]. What really happens is that the story-maker proves a successful “sub-creator.” He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is “true”: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside. The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather art, has failed. You are then out in the Primary World again, looking at the little abortive Secondary World from outside. If you are obliged, by kindliness or circumstance, to stay, then disbelief must be suspended (or stifled), otherwise listening and looking would become intolerable. (p.132)

Fantasy is not the extent to which Faërie is present in the story; Fantasy is how present the audience is within the land of Faërie through the vehicle of the story’s telling.

Realism within the magical otherworld is therefore a vital part of Fantasy for Tolkien.

Fantasy is a natural human activity. It certainly does not destroy or even insult Reason; and it does not either blunt the appetite for, nor obscure the perception of, scientific verity. On the contrary. The keener and the clearer is the reason, the better fantasy will it make. (p.144)

The presence of the moon, the sun, the trees, and mankind itself within Faërie is meant to anchor the audience within Faërie and make the subsequent story intelligible.

For creative Fantasy is founded upon the hard recognition that things are so in the world as it appears under the sun; on a recognition of fact, but not a slavery to it. [...] If men really could not distinguish between frogs and men, fairy-stories about frog-kings would not have arisen. (p.144)

Of course, a story cannot be a fairy-story without straying from reality. At the same time, the further a story strays from reality the harder it is to maintain an easy path into Faërie—one which is not mere “suspension of disbelief” but which allows a fuller presence.

“[T]he inner consistency of reality” is more difficult to produce, the more unlike are the images and the rearrangements of primary material to the actual arrangements of the Primary World. [...] Fantasy thus, too often, remains undeveloped; it is and has been used frivolously, or only half-seriously, or merely for decoration: it remains merely “fanciful.” Anyone inheriting the fantastic device of human language can say the green sun. Many can then imagine or picture it. But that is not enough...

To make a Secondary World inside which the green sun will be credible, commanding Secondary Belief, will probably require labour and thought, and will certainly demand a special skill, a kind of elvish craft. Few attempt such difficult tasks. But when they are attempted and in any degree accomplished then we have a rare achievement of Art: indeed narrative art, story-making in its primary and most potent mode. (p.140)

The sub-created Secondary World of Fantasy requires two things at once: internal believability and the otherworldliness of Faërie. The Secondary World must be realistic and so intuitive that we don’t even have to think about suspending disbelief. It must also be foreign and magical, because Fantasy’s advantage for a story-teller lies in its “arresting strangeness” (p. 139). It is a mix of reality and irrationality, something greater than the sum of its parts.

The simultaneous existence and subsequent tension between the familiar and the strange is so central to the idea of Tolkienian Fantasy that one could say it is the thing itself. Fantasy is not mere worldbuilding, nor mere Imaginative Sub-Creation. It is the potent and paradoxical nature of an Otherworld which is inherently unfamiliar and mysterious while also being knowable and explorable.

The last thing to note here is that in order to work, Fantasy must take Faërie seriously. Said another way: the story must take itself seriously in order to have any chance at accomplishing Fantasy, especially with regard to the otherworldly elements:

... if there is any satire present in the tale, one thing must not be made fun of, the magic itself. That must in that story be taken seriously, neither laughed at nor explained away. (p. 114)

Any serious story will fall into bathos and die in the telling when they undermine their own sincerity (e.g. “Well, that just happened!”). Since a fairy-story depends upon Fantasy and the Secondary World, making fun of the Fantasy itself immediately undermines the integrity of the entire story.

Fantasy & Imagination

Tolkien posits that we can only really enter Faërie through the use of Imagination. Fantasy’s power relies entirely on mental image-making. Thus Tolkien—a philologist through and through—writes: “In human art Fantasy is a thing best left to words, to true literature” (p.140).

Tolkien repudiates the idea of Fantasy happening through painting. He essentially says it cannot happen through a visual medium, because too little is left to Imagination.

He also sheds quite a bit of ink explaining why stage dramas cannot accomplish sufficient Fantasy. It’s not realistic enough. The illusion is too thin. Stage-effects are inadequate. The story unfolding on stage is “not imagined, but actually beheld” (p.142).

The play, when read on the page, leaves room for loads of Imagination. We can mentally shore up the gaps and create for ourselves a world (Fantasy) in which we can have Secondary Belief. But once that story goes from the page to the stage, it pales against our Imagination. We are no longer Imagining, we are receiving. In the gap, Fantasy fails, because we are no longer present in the story; we are instead suspending disbelief.

To be dissolved, or to be degraded, is the likely fate of Fantasy when a dramatist tries to use it, even such a dramatist as Shakespeare.

If you prefer Drama to Literature … you are apt to misunderstand pure story-making [...]. You are, for instance, likely to prefer characters, even the basest and dullest, to things. Very little about trees as trees can be got into a play. (pp. 141-142)

This seems to me like the personal preferences of one John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (the last sentence of that quote should be a dead giveaway to that fact). Tolkien even admits: “To make such a thing [as Fantasy Drama] may not be impossible. I have never seen it done with success” (p.141)

It’s odd to consider, but I believe that Tolkien likely would not have thought the Lord of the Rings movies of 2001-2003 would be capable of accomplishing any true Fantasy.3 We may disagree with his narrow definition, of course, but it is worth understanding it anyway, because it illuminates for us the ways in which Tolkien believes Fantasy and fairy-story can—and ought—to be told.

The Cauldron of Myth

As I hinted at before: we could reduce Tolkien’s Fantasy down to “worldbuilding,” but such a technical treatment largely misses the point. To quote from early in Tolkien’s essay:

The magic of Faërie is not an end in itself, its virtue is in its operations: among these are the satisfaction of certain primordial human desires. (p. 116)

What sorts of desires?

One of these desires is to survey the depths of space and time. Another is (as will be seen) to hold communion with other living things. A story may thus deal with the satisfaction of these desires, with or without the operation of either machine or magic, and in proportion as it succeeds it will approach the quality and have the flavour of fairy-story. (p. 116)

This twofold list is not exhaustive, but Tolkien's hits on two incredibly poignant goals. The magic of Faërie (operating through Fantasy) is meant to:

reveal truths about reality which we cannot survey on our own, and

to bring us into a shared intimacy with others.

To distill this thought even further: Fantasy can help satisfy our longing for Knowledge and Love.

To know and to be known. To love and be loved. What desires are more foundational within the human heart than these? What longings, besides these, can we find at the bedrock of our own souls?

Too lofty? Not for Tolkien. Consider the fact that fairy-stories have their origins within the most ancient and primordial myths, a fact that Tolkien explores at length.

For as long as men and women have walked this earth, they have held in their hearts these radical desires. The oldest stories in existence are the ones most like Fantasy, as defined by Tolkien: open to the supernatural, blurring the line between history and the immaterial, grappling with the nature of reality, defining our place within it, and explaining the deepest levels of Knowledge. Myths ask the questions we most want to know—Where are we? Why are we here? Who are we? What are we for?—and each myth answers in its own way.

This is “story-making in its primary and most potent mode,” which Tolkien said is the aim of fairy-story and the benefit of well-crafted Fantasy (p.140).

Myths like these are dense with meaning. They are artifacts which satisfy (or try to satisfy) our primordial desire to understand the nature of existence. Through their telling, myths impart so many layers of truth that they cannot be fully distilled or reduced to something lesser without jettisoning vital organs of meaning.

If you were to take the entirety of Norse mythological tales as they are written in medieval text, and then ask an AI to summarize them into a new artifact of 10,000 words, you could achieve some level of passable understanding about them, at least at a factual level. But then if you summarized it down to 5,000 words? Or 500? Or a single sentence? How much is lost? Consider the experience of watching a movie and contrast that with reading the film’s Wikipedia plot summary. By distilling the story down to “its message” or “its plot,” you actually lose the purpose of the thing itself. The distilled artifact can no longer be meaning-dense. It at least loses some of its meaning, but quite likely loses all of it. Likewise with myth and fairy-stories.

Tolkien speaks about these mythologies as a kind of Soup, constantly bubbling in a proverbial cauldron. Each generation adds more to the mix. To extrapolate from Tolkien’s metaphor: no two spoonfuls from the cauldron of myth are quite alike, and yet they all have the flavor of Faërie. They all can—if the story is well told, with an eye for primordial human desires—achieve Fantasy, “survey[ing] space and time,” and helping us “hold communion with other living things” (p. 116).

Tolkien even cites the children’s tale of Peter Rabbit as something which comes out of the cauldron and ends up touching upon a deep human condition, albeit in a miniscule way so as to be suitable for children. “The Locked Door,” he writes, “stands as an eternal Temptation” (p.129). We can see the comparison, however faint, between Peter Rabbit’s forbidden garden and the irresistible temptation of Sauron’s One Ring. Both tales touch on the allure of evil, the corrupted nature of man pulling him toward sin, and the tendency for even the most rational and reasonable among us to give in to self-destruction in order to satisfy temporary, selfish desires (e.g. vainglory, power, Mr. MacGregor’s carrots).

Nonetheless, that distillation from the sprawling mythologies of the past down into children’s bedtime stories is precisely the kind of reductive, dismissive definition of fairy-story that Tolkien is trying to dispel. Though even children’s fables touch on the deeper truths because they derive from the cauldron of myth, they are insufficient to fully transmit the necessary deeper truth.

True Fantasy

Considering Fantasy along with Tolkien’s treatment of myth, we can learn that a story with real Fantasy, is not the story that is jammed-packed with dragons and elves and magic rings and every other thing that Professor Tolkien himself made so ubiquitous throughout the then-maturing genre of fantasy fiction.

Instead, the true (capital-F) Fantasy of a story lies in its ability to use those facets of worldbuilding to explore the deeper truths of human nature and reality itself. The ideal fairy-story—relying on its Fantasy—is an artifact so dense with deeper meaning that even the author himself may not be able to fully explain it all outside that story.

Thus, if an author tries to craft a fairy-story purely to transmit an allegedly profound, definable message (or set of messages) to the audience, then its Fantasy will fail because it will not be dense enough with meaning; that is just a morality play, a children’s fairy-tale, sugar-coated preaching, propaganda, or the dreaded “allegory” that Tolkien so famously despised.4 Such parables can and do teach us, since we learn through narrative, but such stories are not Fantastical.

That’s why I say that to equate Tolkien’s idea of Fantasy with worldbuilding is inadequate. The modern term is not mystical enough. To equate the two is to reduce the idea of Fantasy down to something far too shallow, far too brittle. To say that Tolkienian Fantasy is just good worldbuilding is like saying The One Ring and Mr. MacGregor’s Carrots really and truly are The Same Thing. They both may touch on the same thing, but only one is dense with meaning. Peter Rabbit can be distilled into a moral lesson: Listen to Your Mother. The Lord of the Rings cannot be so distilled, even if moral lessons abound from it.

The triumph of Tolkien’s fiction is not due to Middle-Earth being over-stuffed with constructed languages and hand-drawn maps (mere worldbuilding); it is instead that it can, somehow, in some intangible way, feel more real than our own world and make us truly present there, through Fantasy.

✹ ✹ ✹

Thank you for reading part one of this series. Next up is part two—Clifford Stumme’s piece on Tolkienian Recovery—is available here. Clifford explores the idea that Fantasy helps us actually see the real world around us better.

All Parts:

Part 1: The Art of Fantasy (this post)

I recommend you subscribe to Clifford’s publication, Past the Dragon. It’s well worth reading. I highly recommend Clifford’s work, like his recent take on the eras of fantasy literature. I’m thrilled that we can work together to bring you this series.

If you like what you’ve read here you can help me write more of it by liking, commenting, or sharing this piece.

✹ ✹ ✹

Tolkien, J.R.R.: "On Fairy-Stories" in The Monsters and the Critics, edited by Christopher Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin (1984). Page 131. Note bene: from here on out, I must make do with parenthetical notations, or else the legion of “Ibids” will make this post so long it will become undeliverable via email. I’ll reserve the footnotes for additional commentary.

It’s worth noting that Tolkien is not speaking here of any distinction between “high” or “low” fantasy. Those terms relate to whether the story’s setting is meant to connect to the Primary World (ie Earth, our universe). For Tolkien, any amount of Faërie in a story counts as a sub-created Secondary World, even if the story is recognizably earth. Tolkien is certainly known to be a stickler with his narrow definitions, but he does not spurn “low fantasy” as it is often suggested. We know he didn’t like Lewis’s Narnia stories, for instance, but that’s not because it wasn’t separate enough a world. Narnia is a Secondary World of Faërie even if the Pevensies are modern Londoners. After all, Tolkien cites King Arthur and the Beowulf’s Danish Scyldingas as solidly in the Secondary World of Faërie. You can find more info on High vs. Low Fantasy here.

It's entirely possible Tolkien has said something later in life that could illuminate this question. When he wrote "On Fairy-Stories," television was a thing of the future. He lived into the 1970s, though, so its possible he gave thoughts about this at some point. I just don't know. If you know, share it with us in the comments!

And that is much of the reason why Tolkien disliked Narnia. "Sorry Jack, your Biblical morality play could have been an email."

I look at this somewhat differently. Rather than saying that when Tolkien said fairy story we should read fantasy and then when he said fantasy we should read worldbuilding (and acknowledging your caveats on the latter point), I would say the fairytales and fantasy are two distinct genres, and that while Lord of the Rings birthed the fantasy genre, it does not actually belong to it. It is a fairytale.

Of course, Tolkien was not setting out to make this distinction. Fantasy in its modern form did not exist then. He was setting out to defend fairytales against the disdain of realist critics. But this distinction is important nonetheless.

LOTR is really a hybrid of several things, including fairytales, mythology, and the adventure story, a genre of much more consequence then than it is now when air travel means no one goes on a voyage or a march anymore. It is hugely influenced by the Arthurian cycle and functions as a kind of anti-grail story, with its own Arthur and Merlin. But at its very heart, it is a fairytale. Which is to say, at its very heart, it is about virtue and the cost of virtue.

Modern fantasy, I would suggest, took LOTR, stripped out the fairytale elements, and hybridized it with science fiction. The result was to replace virtue with competence at the heart of fantasy. Competence has always been the heart of science fiction. It has become the heart of fantasy also, with highly defined magic systems and schools of wizardry.

Arthur did not establish the round table to teach knights to be more competent fighters, but to be more virtuous knights. Lancelot, the most competent, failed most grievously in virtue. (Boromir is Lancelot.) Sir Gawain survives the Green Knight's challenge not by prowess at arms but by heroic chastity. The round table was always about virtue. So is LOTR, where the mighty, the competent, are not to be trusted with the ring. The only chance is to entrust it to the most humble. It is Frodo's virtue in sparing Gollum that permits the eucatastropic ending that saves the day. Even so, Frodo is immolated by the experience and cannot remain in Middle Earth. It is not merely socially compliant virtue that matters in fairytales, but the high romantic virtue that can sometimes consume those who attain it.

The landscape of faerie is thus fundamentally moral. And thus the physical aspects of faerie, though important, bend to its moral architecture. Which is why Tolkien is right that you can't film fairytales. When you try they turn into fantasies. The Penvensie children are fairytale children, as became obvious when they attempted to film The Lion The Witch and The Wardrobe. You can't start with a child old enough to be as sophisticated as Lucy and then give her three older siblings and have them still all be children. Or, rather, you can't in a movie, so you have to make Susan and Peter teenagers. But you can in a fairy story. E. Nesbit did it with five and even eight.

To further illustrate why you can't film a fairytale, consider this passage from Alan Garner's The Moon of Gomrath:

"But as his head cleared, Colin heard another sound, so beautiful that he never found rest again; the sound of a horn, like the moon on snow, and another answered it from the limits of the sky. ... Now the cloud raced over the ground, breaking into separate glories that whisped and sharpened to skeins of starlight, and were horsemen, and at their head was majesty, crowned with antlers, like the sun."

You can, as Tolkien says, imagine that, but you cannot picture it. You cannot reduce it to images on a screen. You can imagine, but cannot make, a sound so beautiful that you will never know rest again; you can imagine, but not hear, a sound like the moon on snow. This is faerie. It is the landscape of the soul. It is not fantasy and it cannot be filmed.

My personal interpretation of Fairy Stories, as opposed to generic fantasy stories, finds the former using fantasy elements yet deeply rooted in history, traditions, and folklore within a specific geographical region