In my last post, I began to explore why warriors wield the weapons they wield. This is part 2 of that exploration.

If you want to catch up, you can read part one here, but if don’t feel like it, here’s a summary:

I began with the premise that soldiers and warriors (being regular people, like you and I) generally do not like dying and—shockingly—try to avoid that. In pursuit of their survival, warriors are always locked in an "arms race" of equipment and tactics against their expected enemies. This "arms race" affects friend and foe alike, which means that certain tactical cultures develop, which I compared to 'meta' tactics within competitive gaming. Thus, I introduced the idea of “tactical antagonistic co-evolution,” the process by which weapons and armor develop in dialogue with one another based on the expected threats of the enemy and the tactics that warriors use to overcome those threats.

This is part two of that exploration, where we will begin to evaluate the fantastical through the lens of this tactical evolution.

As I said last time, these rules of co-evolution…

…determine when a fantastical story leaves the realm of the grounded and immersive and veers into wish-fulfillment and cringe.

Which means, here in part two, we’re gonna look at some cringe-worthy “weapons” and “tactics”. Yes, I will make fun of them, but more importantly I’ll explain precisely why these examples are unreasonable and what about them pulls them out of the “badass” category and into the “cringe.” Then I’ll evaluate what the storytellers could do instead.

Let’s start the tour with a weapon that I find completely ridiculous and ridiculously common.

Whips.

Ah, whips. They’re the standard kit of plucky explorers, femme-fatale superheroines, and masked vigilantes the world over.

They are also terrible weapons. They require a precise distance-to-target, they need lots of space to work, they can harm any friendly comrade near you, they are stopped by even basic cloth armor (i.e. thick clothes), and they do not disable an enemy.

After all, let's consider what whips are actually used for: forcing compliance among animals and slaves (and if you need any more proof of slavery's barbarism, consider the implications of why those two things are in the same category). In both cases, the weapon is used against defenseless targets with the goal of creating pain but without actual, irreparable harm. A whip is meant to create fear and momentary compliance. Is it not meant to cause permanent damage. This is similar to the corporal punishment of "lashing,” where the assailant uses a switch or rod; the target is stationary, defenseless, and not *actually* disposable.

Meanwhile in battle, as we discussed last time, you must rapidly dispose of your enemy or you will die. Why on earth would you willingly bring something that is designed to not kill?

Special Dishonorable Mention for whips has to go Vinland Saga. When I first imagined this piece I asked Old Friend Dunmore what was the most absurd fantasy weapon he’d ever seen. He said “chain whip” and I almost decided to just give up. He pointed me towards the anime Vinland Saga and this little number:

This isn’t how chains work. They don’t stick to things. There’s no anchor, so it will immediately fall slack onto his shoulders whether the wielder is pulling or not. And if this chain had hit this man with enough force to wrap itself neatly around his head, his head would likely already have collapsed, or the g-forces would have popped a link.

Then again, what would you expect from a show that puts ancient Greek biremes in 11th Century Wales?

What the Storytellers Could Do Instead: Assuming the whips aren’t being used in a more natural “intimidation” context, give whip-bearer a spear, club, or staff. They could still whip it around in circles and be all dramatic, but they won’t look like idiots who brought brass knuckles to a gun-fight.

Which reminds me…

Brass Steel(?) Knuckles

Here’s a little diddy from the 2004 film King Arthur, showing Sir Bors with his specialty weapons.

Brass knuckles are a thing, but only in contexts where fighters cannot get access to real weapons or where the legal ramifications for wielding those weapons would be so great so as to make it inadvisable.

These are… not that. This character’s special move is to punch his enemies in the chest a few times and then slide the blade of his (?)fisticuffs(?) over their throats. You know they can work because there’s blood on ‘em!

Would they actually work though?

Do an experiment for me, dear reader: extend your arm out in front of you as if you just threw a punch. Hold it there. Now imagine there’s a blade running down the outside of your forearm, wrist to elbow. Now imagine that blade just slit a bad-guy’s jugular. How close to you would that bad-guy have to be in order for that to have just happened? His throat would be at your elbow and your fist would have to be way past his head. Your feet would have to be entangled with his. He’d have to be solidly in hugging distance for this work. And he’d have to be unarmored. And unarmed. And stationary.

Good thing our boy Bors has a good helmet and lots of strong armor to protect him while he maneuvers in close—oh wait.

What the Storytellers Could Do Instead: Give him basically anything else. A kitchen knife would be better. If you want him to be big and strong and scary, try an ax, or a warhammer if you must.

Putting the Wall in Shield Wall

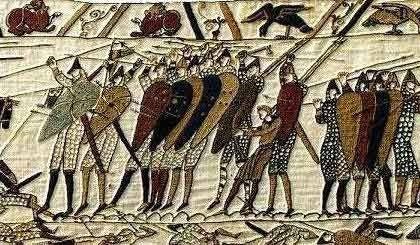

Moving to tactics, now. There’s a certain trend in depictions of pre-modern battles where one group of soldiers will form a “shield wall.” A shield wall is a veritable historical tactic! When you’re going into combat, it’s a good idea to get close to your comrades and form a protective barrier, and it’s a good idea to point all your weapons outward towards the bad guys.

Note that a shield-wall has overlapping shields, a tight formation of men looking out over those shields, with plenty of ways for those men to stab or otherwise harm the enemy in front of them. Any enemy would have a hard time getting close enough to do damage (because of all the pointy bits), but ranged attack would be equally ineffective because of all the shields. That’s what a shield-wall looks like.

It will not look like a literal wall of shields.

This literal wall of shields theoretically protects the men behind it. However, it also blinds them, immobilized them, and makes them incredibly crowded. If every shield is meant to represent one warrior, how would they actually go about creating that wall? One man kneeling on the ground, another man crouched over him with his arm extended, another man standing above and leaning over to protect their heads, then another man leaning even farther over to protect the third guy’s head?

How would they move? How would they fight?

Meanwhile, their assailants (in this case, the English army charging from the right) are currently in no danger whatsoever. There are no spears or weapons of any kind turned against them. The attackers are free to smash at the shields with their own weapons while the defenders cannot even see them. The attackers can slip their blades through the cracks and there is nothing the defenders could do to prevent it. Consequently, this sort of thing has no precedent in history because people in history (much like people today) generally try to not die.

There are, however, similar formations used when a group of soldiers are under missile-fire. If they cannot retreat and there is no imminent threat of close combat, the soldiers might form something like the literal-wall-of-shields to defend themselves.

Notable examples are the Roman testudo and the Uruk-hai at Helm’s Deep (in the movies). But you would only do this if you were under sustained ranged attack and there was no threat of closing with the enemy.

What The Storytellers Could Have Done Instead: Form a normal shield wall and let us see the characters actually fight in a scrum, face-to-face. In movies, though, I think there’s little chance of this happening, since in reality there is probably nothing behind that wall of shields and this setup actually allows actors to slam into this “unseen enemy” without worry about anyone’s safety.

Metal Shield-Rims

Speaking of shields, they did not have metal rims. At least, there is no historical evidence of metal-rimmed wooden shields like the one below. These sorts of shields show up in fantasy media a lot, especially D&D-adjacent properties and video games of all stripes.

This isn’t cringy, it’s just a pet peeve of mine.

The logic is that a metal rim prevents the shield from cracking in the event that it’s hit on the rim with a bladed weapon (especially a heavy axe). You could also jam the rim into someone’s face. Now, cracking from the rim was a problem, and it’s one that ancient and medieval warriors spent time and effort solving.

The first problem is that this is a waste of metal and metal is not cheap. It also makes the shield heavier which is a very bad thing (perhaps counter-intuitively). You want a shield to be sturdy, but not heavy, since you may need to move it very quickly to save your own life. So, you want strong, but also lightweight.

What To Do Instead: most wooden shields would have had some kind of organic material like rawhide around the edges, bound with cord threaded back and forth through the shield itself. The rawhide protected the edge and bound the planks together, all while being incredibly lightweight and relatively cheap. As an added bonus, a blade could actually get stuck in the rawhide edge allowing the defender to flick his wrist, spin the shield, and twist the blade right out of his opponent’s hand.

Dain, Lord of the Iron Hills Dome

Back to the cringe. One of the worst fantasy battles I have ever had the displeasure of watching was “The Battle of the Five Armies,” in the eponymous, third part of The Hobbit movie series (2014).

I hadn’t seen this until quite recently and—my goodness—it is so bad.

For a blog post about cringe fantasy combat, the ill-conceived Hobbit movies are what we’d call a “target rich environment.” I’ve had to restrain myself and pick only one, so I’ve settled on the deployment of DAMADS: the Dwarven Anti-Missile Air Defense System.

Here’s how it works: on one side we have an army of Elves led by Thranduil. On the other side, atop a hill, we have an army of Dwarves, led by Dain, Lord of the Iron Hills. Battle commences when Dain orders his goatry (think “cavalry,” but with goats) to charge even though this would surrender his defensible position on top of a craggy hill.

Then, the Elves do the only thing that Elves ever, ever do (apparently) and fire a volley of arrows at their enemy. Just one. Every one of them shoots a single arrow. Then the greatest archers in Middle Earth just… wait to see how it turns out. I guess.

Meanwhile Dain, visible below on his war pig, shouts an order to deploy DAMADS. His artillery men, despite being several hundred yards behind him and out of sight behind the hill manage to hear this order perfectly over the roar of charging goatry, and they then all shoot bolts at exactly the same time.

Those bolts, as you can see in these pictures, have some sort of spinning… propellers(?) … on their ends which then scatter the Elven arrows and send them falling harmlessly to the ground.

As an added bonus, each one of DAMADS’s bolts goes on to land among the enemy Elves with enough force to (apparently) throw dozens of Elves flying through the air.

The Elves, shocked by this, decide to send another single volley of arrows, launching all of them together. At the same time. At the same angle. Good thing they waited too, because that means DAMADS has been reloaded and the whole thing can happen again!

It’s like Israel’s Iron Dome! The enemy is launching hundreds of unguided missiles at our troops? Fear not! Our computer-accurate missile system (Dain’s eyeballs) can detect those threats and deploy counter measures (by shouting) to disable those missiles with guided precision (luck).

This just raises so many questions. How did the Dwarves know the right distance, given that the artillery cannot see their target? How did they get the angle of fire just right? How did they get the timing right? How much did they practice this? Are they that experienced with knowing, and judging, and executing the rate of travel of various projectiles? How did they develop this weaponry? Had they ever tried this tactic in the field? Apparently not, since the Elves are quite surprised.

But also: how do all the bolts have the exact same trajectory? How do they all travel perfectly parallel?

And how, above all, did they know that the Elves would only fire one volley at a time?

If the Elves had behaved like every other archer in history, they would have simply let their men loose their arrows at their own will, at which point the Dwarves would be pelted with the deadly things at fairly constant rate, and before long the fields of Erebor would be littered with raw goat-kebab.

Then, just to give me an aneurysm, the corresponding battle has not one but two different literal-walls-of-shield shield-walls.

What the Storytellers Could Do Instead: It’s fun to watch characters struggle with problems and overcome them through strength or ingenuity. (DAMADS is not that. DAMADS is “gotcha! Betcha didn’t see that coming!”) Instead, let the characters struggle with the basic, intuitive problems of the scene.

Thranduil has an enemy army on high ground, which would be difficult to dislodge. It’s a problem for any field commander; let it be a problem. Dain would look quite clever if he held his ground and shot simple, normal, non-cringe artillery bolts at the Elves. If the Elves responded with a remarkably deadly hail of arrows, then it would be their turn to look strong and impressive, since they just solved a problem by forcing their enemy to abandon his defensible position.

Then, maybe Dain would have to advance down the hill in order to force his enemy into close combat to eliminate the threat of the arrows. That would be a major risk, but it would be daring, brave problem solving! And then the producers can still get whatever big melee brawl they want. They’d still get a big downhill charge, they’d still show their characters being bold and brave, taking punches and delivering counter-blows… And it would be a whole lot less ridiculous.

How to Avoid This

If you’re like me, you want to avoid doing this in your writing. Here’s a few quick things to keep in mind.

Historical Precedent: if it’s never happened before, there’s probably a reason. If your super-cool imaginary battle tactic is entirely different from those tactics developed by people whose lives depended on their tactics working, then your imaginary battle tactic probably won’t work. Sorry. Re-evaluate. Your story can still be good, I promise.

Simplify: If you didn’t notice, all my advice above about What To Do Instead centered around making things simpler, cheaper, and more intuitive. We usually don’t get to “wacky” or “cringe” without first passing through “complex.” Don’t overthink it.

Versatility > Specialization: similarly, stick to weapons, tactics, and armors that address lots of potential problems and threats. Whips are useful in a small number of settings. DAMADS is useful literally only in that one scene where everything is just right. And hyper-specificity is why they don’t really make sense. If you need to bend the setting (or bend character decision-making) to best show off the weapon, then the weapon wouldn’t exist.

What About the “Rule of Cool”?

Critics might say I’m being too harsh, I should just let fun things be fun, I should “let the kids play, ref,” etc. etc. … And you know, that’s fair! I am very aware of how nit-picky, grumpy, and generally curmudgeonly I am being. You can, if you want, break the non-existent ‘rules’ and follow the Rule of Cool. If people are having fun, go with it. Sure. Why not.

As I’ve said before: this is just my opinion (which you can disagree with (and disregard)).

But while we’re talking about my opinion: I think our stories should go deeper than just “having fun.” I’ve written before about the value of having “realistically unreal” worlds and settings, and about how emotional investment and the lasting impact of a story is first predicated upon the suspension of disbelief.

Furthermore, if we as fantasy readers and writers think that the fantasy genre is more than children’s fables and pixie dust, if we believe that fantasy is an avenue to a deeper understanding of reality, if we think that this genre ought to be taken seriously by those who haven’t bought in yet, then it means we have to take it seriously ourselves.

This stuff does matter to audiences. After all, The Lord of the Rings movie trilogy relied (mostly) on Tolkien’s own implicit understanding of medieval warfare, and its action sequences are unforgettable. The Hobbit movies, meanwhile, are a farce. The former remains a pinnacle of cinematic achievement while the latter had no cultural impact beyond a cautionary tale about bloated narratives. There were plenty of other reasons for that: great screenwriting, respect for the source material, better effects, a little thing called “plot.”

But a quick comparison between the Theoden’s Ride of the Rohirrim and DAMADS really encapsulates just how those two stories see themselves, and how audiences see them in turn.

I’m not saying don’t have fun. I’m saying let’s not only have fun. As readers, our attention deserves better. As storytellers, our audience deserves better.

✹ ✹ ✹

If you like what you’ve read here and want me to keep making stuff like this, you can help me do that by liking, commenting, or sharing this piece. You can also see all my writing by visiting this page.

✹ ✹ ✹

✹ ✹ ✹

Solid writing. Are you going to mention Wagenburg in the future? Well presented in best works of Sapkowski. No, not in Witcher. I his less known but greater historical fantasy series Hussite Trilogy.

My friend who wrote a popular mega-dungeon is continually mystified at the Facebook groupies who comb through his work asking things like "how much would this golden statue weigh?" as though they expect him to know, or care. The game of GOTCHA is alive and well on the Internet.

I don't know a lot about early fandom, but there's also this. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egoboo