If you like what I do here, you can support me simply by liking, commenting, or sharing this piece. You can also see all my writing by visiting this page.

✹ ✹ ✹

Where Do Kingdoms Come From?

In the conversation around my post about political legitimacy and its relationship to violence (and religion, and history, and…), I had a few comments that were not just about the maintenance of pre-modern rulership, but the origins.

Sure, a monarch can cement his or her legitimacy through religious mandate or the consent of the governed, but how would they, you know, get a kingdom to rule in the first place?

This is actually a much weirder question than you might think. And it’s a question I’ve spent a long time thinking about in relation to my own worldbuilding and the stories I want to tell.

So in today’s post I’m going to explore that question. I’m going to look around at the stereotypical western fantasy setting and ask…

…how did we get here, exactly? Or at least, how could we get here.

To answer that question, and to shed some light on where kingdoms come from, let’s take a look at a few “first” kings. In particular, let’s look at two of the archetypal kingdoms for the fantasy genre (at least in the public consciousness of the Anglosphere): France and England.

What Makes a King?

Before I dive in, let’s take a quick detour and ask about the king himself1. If we were to ask a Family-Feud style panel of average people “how does someone become a monarch?” I am willing to bet we would get two prevailing answers:

They inherit it from their parents

They win it through conquest

Neither of these are wrong—we’ll see both origin stories crop up quite a bit in the history below—but nor are these reasons remotely sufficient. As we’re going to see, both of these things presuppose there’s an empty throne for someone to sit down on, a crown that is currently on nobody’s head. But our question is: where did we get that crown?

Je Suis le Roi?

Let’s begin this history with two simple questions: who was the first king of France? And how did he come to be the first king of France?

We have simple answers: King Philip II Augustus was the first man to call himself King of France (Rex Francie). And he became king when he was crowned co-king alongside his aging father, King Louis VII, in AD 1179 as a way to make clear the succession. When Louis died the next year, Philip ruled in his own right until 1223, and he starting using the title “King of France” in 1204 (after trying it on informally for about 14 years).

So there’s our answer: the first king of France was Philip the Second, and he became king by inheriting it from his father…

Now read that sentence again, and hopefully you’ll see how self-defeating it is. How can the first king be Philip … the second? And exactly what exactly did he inherit if not, you know, France?!

Now, I’ll warn you, this is about to get a bit wonky. I’m going to mention a lot of kings and peoples and centuries. If you can’t keep it all straight, it’s alright. There’s a

method to my madnessmadness to my method, and I’ll wrap it all up below.

Where Do We Begin?

There are two decent starting places for a history of medieval France: either the reign of Charlemagne as “Emperor of the Romans” in the early ninth century, or the end of the tenth century with the accession of Hugh Capet as King of the Franks (not “France!”).

See, Charles the Great (in French: Charles le Magne ~~> Charlemagne) was a Frankish (not French!) king who ruled over vast swathes of Western and Central Europe and united these lands under a single administration for the first time in centuries. As a reward for defending the power of the papacy, the pope crowned Charles as “emperor of the Romans,” in a quasi-refounding of the Roman Empire.

Charlemagne died in AD 814, and to make a complicated story palatable: over the next two centuries that Frankish empire fragmented, congealed, waxed, waned, and ultimately solidified into two distinct states: one would become Germany (via the Holy Roman Empire) and the other would become France (via the Kingdom of the Franks).

Those two nations’ histories really diverged in the late 900s, in part thanks to the election of Hugh Capet as King of the Franks in 987.

And “King of the Franks,” was the title that our boy Philip inherited, from a direct line of fathers to sons, 193 years later.

So thanks to Hugh Capet we could choose 987 as the year the Kingdom of France began, even if it wasn’t quite called that yet. Since “the Franks” more or less morphed into “the French,” we can do the same sort of hand-wave logic with the kingdom title and call it a day, right?

Except Hugh Capet wasn’t really the first anything! He wasn’t the first King of the Franks, he wasn’t the first King of the Franks to rule the geographic area we call France, and he wasn’t the first French speaker to do that or anything either. He’s only significant because of hindsight, because his rule was the beginning of a 400-year period were “France” was ruled by one family, a chain of events so unusual that we literally call it the “Capetian miracle”.

To find the first King of the Franks we need to go back further. WAY further. More than 400 years further, to a guy named Clovis. Clovis united all the Franks under one crown and named himself The King of the Franks. At that time there were lots of kings of different Frankish groups and they all worked for the Roman Empire (the original Roman Empire, not Charlemagne’s reboot), but then the Roman Empire went belly up and Clovis was the man on top of the dogpile that ensued. That was in 509. But he was a king for twenty eight years prior to that, just as one of many Frankish kings… So he went from being one of many men to be a king of some Franks to being the king of all the Franks. That distinction does matter, but does that make him the first King of France?

Let’s just take stock for a second.

The answer to the very simple question—who was the first king of France?—has no less than three possible answers, spread across eight hundred years, and all of them are correct.

Philip II was the first guy to call himself that in 1204

Hugh Capet in 987 was the starting point for French political consciousness even if no one knew it at the time

And Clovis holds the bag for being the “first king of the thing that will some day in the far future morph into France.”

We are literally back to the time of the original Roman Empire; Clovis was born in 466, before Rome fell in the West. We’re a full millennium before Joan of Arc and it’s still just kings all the way down! (Heck, when 19th century French nationalists wanted mythologize the earliest-possible foundation “moment” of France, they turned to Vercingetorix—the Gallic king who fought against Julius Caesar!)

This means that if we want to get anything that resembles a complete answer to the “first king” question, we need to do a deep explanation of the Frankish nation, its roots among other Germanic nations, their cultural values, their systems of legitimacy, and the long history of that people’s interactions with and within the Roman Empire. That’s way too much for this post.

So forget France! Maybe England is better?

“King o’ the Who?”

Spoiler alert, England is not much better.

To begin with, there’s a similar problem as what happened with Philip II of France: the first “king of England” (Rex Anglicae) was actually Henry II in the 12th century, but again this is a linguistic quirk. Prior to that, the title was “King of the English” (Rex Anglorum). It was a people, not a place. That was right around the time of Philip II, by the way, in the 1180s, so I guess we can call it an “eighties trend,” like big hair and shoulder pads. Let’s go back further.

Sweeping histories of England usually begin in AD 1066 with William the Bastard the Conqueror who (you’ll never believe this) conquered England. And the “starting point” of 1066 makes sense because it is from William that every other English monarch traces his or her lineage, down to the present day. William began building the state institutions that will survive down the centuries.

But obviously, William was conquering an existing kingdom; his conquest would turn out to be a major moment in the history of Europe, but it sure wasn’t the beginning of England. Where did the kingdom come from?

For that we need to back another 140 years to King Æthelstan, who was the first(ish) king to call himself “King of the English,” starting in 928. Once again there’s a certain amount of sense to this answer, since Æthelstan controlled the whole territory we call “England” after wrestling control of Northumbria away from the Danes (i.e. Vikings). After him, England was a clear entity, and it was the entity that William conquered. If there’s a “right” answer, it’s probably Æthelstan.

But once again there’s a problem, because Æthelstan was already a king several times over when this happened. He was already King of Wessex and of Mercia (these are regions within modern England). More frustratingly (for us), he had previously used a similar title: King of the Anglo-Saxons. That title had already been in use for nearly a century, going back to Æthelstan’s grandfather, Alfred the Great of Wessex. Alfred created that title as a way to legitimize himself against the foreign (to 9th century Britain) Danes and Norsemen who had invaded and overthrown the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

So aside from the question of “King of England” vs. “King of the English,” we have another debatable term: Who are “the English,” and how distinct are they from “the Anglo-Saxons” and when does such a distinction develop? It’s even a very thorny question just to figure out whether “the Anglo-Saxons” are a group at all or if instead its just a catch-all term for a wide group of people with other sub-groups who have their own sub-groups (e.g. East Anglians, West Saxons, Mercians, etc.)

And if we go back further into that Anglo-Saxon period before Alfred, there are other kings who had sufficient lordship over the area we now call “England” that its entirely possible one of them should be called the first king of England. King Offa of Mercia called himself Rex Anglorum—King of the English—a full two centuries before Æthelstan did! That title wasn’t passed down, but does that matter? Do we care?

Now we have to do a deep dive into the centuries-long story of how “English” identity developed and evolved and how the disparate institutions that could be seen as “England” fit into that identity. That’s way beyond the scope of this post.

So who was the first king? Was it…

King Offa (died AD 796), the first to call himself Rex Anglorum (I think)?

King Alfred (d. 899), the first ‘king of the Anglo-Saxons’ ? He could be our answer since he was the progenitor of…

King Æthelstan (d.939) the first “King of the English” to actually pass his title on and down through the generations?

Or King Henry II (d.1189) the first one to actually call himself king of England rather than “the English?”

And if we really wanted, we could trace Alfred’s line back into the earliest days of Wessex, since Wessex was the “thing that would one day morph into England,” but that takes us back into very foggy territory around… the fall of the Roman Empire. And don’t even get me started on Arthur.

We have the same problems as with France! Except now we have at least four “first kings” instead of three!

What Have We Learned?

I hope you realize by now that I’ve deliberately set myself up to fail; “Who was the First King of X?” is mostly a broken question. Any answer you get will have certain assumptions and caveats baked-in. But our failure to answer “who’s the first king” can actually tell us quite a lot about how kingdoms develop.

So now let’s look at the two histories above and draw a few lessons out of the mess, not about kings, but about kingdoms and their origins.

Kings Precede Kingdoms

This should be clear from all of the above, but it bears saying explicitly: you can’t have the ideal of “a realm”, you can’t have an institution called “the crown” for someone to inherit or claim or conquer, you can’t have a kingdom at all, until you first have a king. Kingship as a concept was already very well established in these nations—over the course of centuries—long before the particular institutions of England’s or France’s monarchy.

Kingdoms Come From Whatever Came Before

In all these cases, the institutions of monarchy and even the many iterations of kingly titles all derived from whatever had come before.

All the possible “first kings” had their part in crafting and shaping the kingdom-institutions, but every single one of them was already a king of something or someone before particular naming conventions and titles we investigated came into play. And that’s to say nothing of the many other preexisting forms of royal legitimacy these men relied upon.

So what came before?

Kingdoms Arise from Nations, Generally

In modern parlance, a “nation” is synonymous with “country, state, or polity.” We think of a nation as an autonomous government, like the United States, China, or Namibia. This isn’t quite right. Instead, a nation is historically understood as a collective ethnic group that (generally) lives in a particular zone (though it can move) and they generally share some sort of founding myth (usually dovetailing with a shared religion). A nation might have many political subdivisions (like the Franks before Clovis), or they might be subordinated under a wider multicultural government, or they might not have a state (ie a government) of any kind. Strictly speaking, the USA is not a nation, but the American Indian tribes like the Oglala Sioux or Shawnee are nations.

Historically, nations often end up organized under single leaders that more or less fit the definition of ‘king.’ This makes sense, given that cultural identity markers like language, religion, and history are major factors within the engine of monarchical legitimacy. We humans are good organizers and collaborators, but we generally like having “one of our own” at the top leading us.

Sure, that “representation” doesn’t look the way we modern liberals2 would expect, but it is certainly easier for a nascent kingdom-state to enforce and legitimize its rule over cultural groups that are the same or similar to its ruler—even if that rule is expanded through violence. Such was the case with Clovis, who violently expanded his power by conquering other Frankish kingdoms and rolling them into one. Despite that violence, the Kingdom of the Franks survived long enough to morph into something new: France. Similar story for Alfred and the generations that followed, including Æthelstan.

Kingdoms Arise *in* a Place, not *from* a Place

To a modern audience, this is probably the weirdest part of this whole question: kingdoms do not come into being with clear borders.

The nations that produced these “first kings” were not intrinsically connected to the land they lived on. They did not call themselves Franks because they lived in Francia; they started calling it Francia because the Franks lived there. Before that it was Gallia, named for the Gauls, who used to live there.

It was a much, much later ideological development for kings to identify with the land rather than the people. And it’s worth noting: in both the examples we listed the kings in question had very good reason to do so.

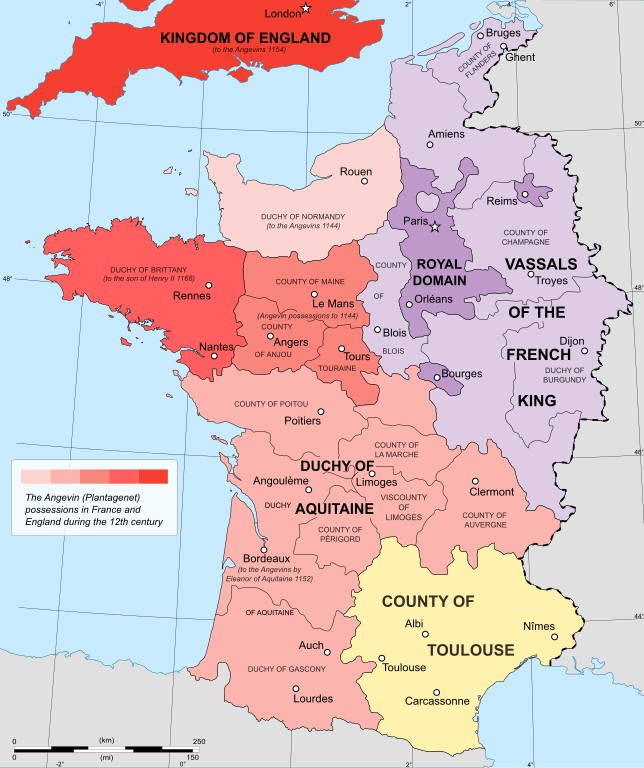

Henry II of England and Philip II of France were actually locked in a struggle for dominance over the geographic area of France. Henry actually controlled most of France and he identified as culturally French. By changing from “king of the English” to “king of England,” he could subtly disassociate his right to rule from that English identity which he did not fully share. Meanwhile Philip’s change from king of the Franks to king of France was a way to indicate that he ought to control the whole geographic area, regardless of who might live there.

The point is that the borders of all these “kingdoms” started as practical, not ideological. They began as “whatever territory the king controls” and only slowly morphed into distinct, geographic claims.

The Fantasy Kingdom

When we think of the stereotypical fantasy kingdom, then, what we’re actually looking at is mature, highly-centralized states. The kings in these settings ought to have quite a variety of legitimizing claims, like divine mandate, historical precedence, and ethnic or nation-focused heritage. These kings might have personal popularity or significant military strength, but unless they are creating something new the question of personal glory ought to be secondary to the preexisting institutions which they inherited (by blood or by deed).

Let’s return for a moment to Aragorn (and indulge me while I once again explain how amazing Tolkien’s work truly is). J.R.R. Tolkien implicitly understood these dynamics, and we can see them at work in the accession of Aragorn the Second to the throne of Gondor and Arnor. On one hand, this is something “new”. There hadn’t been a king of Gondor in centuries and Aragorn’s coronation is so monumental that is demarcates the Third Age of Middle Earth from the Fourth Age.

However, it is not entirely new. Aragorn has personal glory for helping defeat Sauron, and he has “divine mandate” of a sort via Gandalf the White, but ultimately his legitimacy—his kingdom—is derivative of that which came before. He has a claim to be King of Gondor and Arnor because he is one of them; he shares their history, values, language, and beliefs. He is the descendant of the old kings, and so his kingship precedes the actual political institution he later heads (hence Aragorn the Second, not Aragorn the First).

Meanwhile, he also inherits (by deed, not by blood) the preexisting institutions: Faramir the Steward makes way for him; Minas Tirith’s houses of healing accept his lordship; the Elvish lords proclaim him; the preexisting lords of men, in the persons of King Eomer of Rohan and Prince Imrahil of Dol Amroth all swear loyalty to Aragorn and his heirs.

The borders of his kingdom, too, are amorphous: they could extent as far north as the Argonauth (the big statues below) or they could extend farther, to include Weathertop, the Grey Havens, and the Shire. In the event, these northern lands of Arnor are incorporated into Aragorn’s kingdom because he has the strength and political legitimacy to do so (with the help of folk like Meriadoc Brandybuck).

Compare Aragorn’s story to that of Tolkien’s other kingly hero of Men, Túrin Turambar, who tries several times to found kingdoms out of nothing: refounding his father’s kingdom of Dor-Lómin, creating a new state of refugees at Amon Rûdh, then taking over as a pseudo-warlord in Brethil… In each case Túrin lacked any preexisting nation, any semblance of a state, any lever of legitimacy except personal glory and reputation. And he failed every. single. time.

I don’t know about you, but I think that’s just one of the ways that historical-realist principles actually make fantasy and speculative-fiction storytelling way more interesting, even if none of those principles show up explicitly on-screen.

And that’s why I’ll keep writing about them.

✹ ✹ ✹

If you like what you’ve read here and want me to keep making stuff like this, you can help me do that by liking, commenting, or sharing this piece. You can also see all my writing by visiting this page.

✹ ✹ ✹

✹ ✹ ✹

or herself. There were female kings, like Jadwiga of Poland. But also obviously everything we’re saying relates to monarchs more broadly.

by “liberals” I mean to reference “liberalism,” the ideology that gives us things like representative democracy and individual rights and liberties. I’m not talking about political identities within that discourse.

Oh wow. I have never thought of Tùrin this way. Now I'm thinking that the elven socities, well into the Third Age, could not "develop" (from a human perspective) into medieval kingdoms like Gondor since the elves lived too long and remembered too much to form a national identity. They, in a sense, still lived in an enlarged tribal states.

"Supreme executive power resides in a mandate from the masses, not some watery tart..."