Embracing Reality by Escaping to Faërie

Pt. 3 on Tolkien's "On Fairy-Stories," with Clifford Stumme: Escapism, Technology, and Endorsing Reality

This is part three of our four-part series on J.R.R. Tolkien’s influential 1947 essay, “On Fairy-Stories.” All October long, I’ve teamed up with Clifford Stumme of Past the Dragon to explain and explore what Tolkien says about the purpose, value, and methodology of fairy-stories.

As Clifford explained last week, Tolkien held that “effective Fantasy”—by which Tolkien meant a well-explained, believable, and fantastical Secondary World— “provides three overarching benefits to readers: Recovery, Escape, and Consolation.” We’ve already looked at Tolkien’s ideas of Fantasy and Recovery. For the best experience we recommend you read those essays first before moving on to this week’s topic: Escape.

Is Escapism a Good Thing?

Today, just as in Tolkien’s day, the fantasy genre is so often maligned as being naïve and “escapist.” I could look for proof, but if you’re reading this then you probably don’t need any. This is one reason why fans of the genre ought to familiarize themselves with “On Fairy-Stories,” or at least its ideas: Tolkien’s entire essay is devoted to the defense of the fairy-story.1

Nowhere in the essay is his defense more clear than in his section on Escape. Here, perhaps more directly than anywhere else in the essay, Tolkien combats the realist critics of his beloved Artform.

Though fairy-stories are of course by no means the only medium of Escape, they are today one of the most obvious and (to some) outrageous forms of “escapist” literature; and it is thus reasonable to attach to a consideration of them some considerations of this term “escape” in criticism generally.

I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which “Escape” is now so often used. [...]

Evidently we are faced by a misuse of words, and also by a confusion of thought.

Tolkien goes on to contrast two competing concepts, each being definitions of “escape.” The first is mere “escapism,” a kind of fancy or daydream which encourages us to avoid our problems or duties. This is the form of escape that critics of Faërie so quickly dismiss. This escapism is indeed problematic. However, Tolkien contrasts mere escapism with capital-E Escape, which he says is “very practical, and may even be heroic.”

He writes:

Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it. In using escape in this way the critics have chosen the wrong word, and, what is more, they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter.

The Prisoner values the real world and wishes to experience it. The Deserter scorns reality and seeks to flee it. The Prisoner is someone who yearns against unjust restraints, who desires that which is good, and who strives with whatever means he has towards the betterment of himself and the world. The Deserter, meanwhile, is the man who looks at reality and despises it, choosing instead to live in a disconnected denial of his own life.

The critics of fairy-stories conflate these two characters, saying that all such stories must surely encourage desertion or flight (escapism), leaving no room for those who would resist imprisonment (via Escape).

The Deserter is rightly derided, but criticism of escapism goes too far if it includes condemnation of Escape. By upholding so-called Real Life as the only measuring stick of a story’s value, the Realists actually make it impossible to write a story which might envision a better life.

Not only do they confound the escape of the prisoner with the flight of the deserter; but they would seem to prefer the acquiescence of the “quisling” to the resistance of the patriot. To such thinking you have only to say “the land you loved is doomed” to excuse any treachery, indeed to glorify it.

In other words, to deride all imaginative story telling is to simply shrug at the world in general and say “it is what it is,” without an ounce of hope. It is heroism as naïveté ; pessimism as truth; evil as enlightened realism.

In some ways the Realist makes the same mistake as the Deserter, who looks at things, says “it is what it is,” and then denies his own part in it.

Escapism is a narcotic, numbing reality so that we can ignore it more easily. True Escape, as Tolkien envisions, is instead an endorsement of reality and a desire to embrace it more fully.

Escape, properly done, is meant to be a kind of enlightenment, not inebriation.

How can you know the difference? Simple: are we trying to escape from something good and towards something evil, or escape from something evil and towards something good?

Escaping From and Towards

After defining Escape in this way, Tolkien goes on to explain many of the specific things from which Fantasy can help us escape. He lists four things: the Robot Age, general hardships, ancient limitations, and death (but also, interestingly, deathlessness).

Like Tolkien, I’ll touch on each, spending the most time on the first.

Archaism and Anti-Industrialism

This might come as a huge shock to you, but the man who wrote a story about living trees enacting vengeance upon an industrialist wizard and his giant factory-fortress was, in fact, unhappy with the technological advancements of modernity.

At this point in “On Fairy Stories,” Tolkien begins a passionate criticism of what he calls the Robot Age, with its noise, its endless machinery, its destruction of the natural world, and its emphasis on technological progress as a goal in and of itself.

Now, Tolkien’s thoughts on technology are a topic well-beyond the scope of this series, but I will give the topic a brief treatment before moving on to how they relate to Escape.

Tolkien’s views on technocracy are clearly informed by his own love for the English countryside, a romanticism which was likely buffeted, at least in part, by his own privileged class as an Oxford professor. It is easier, after all, to mourn the loss of the scythe and the rise of the engine-powered harvester-tractor when you yourself are not swinging the scythe.2

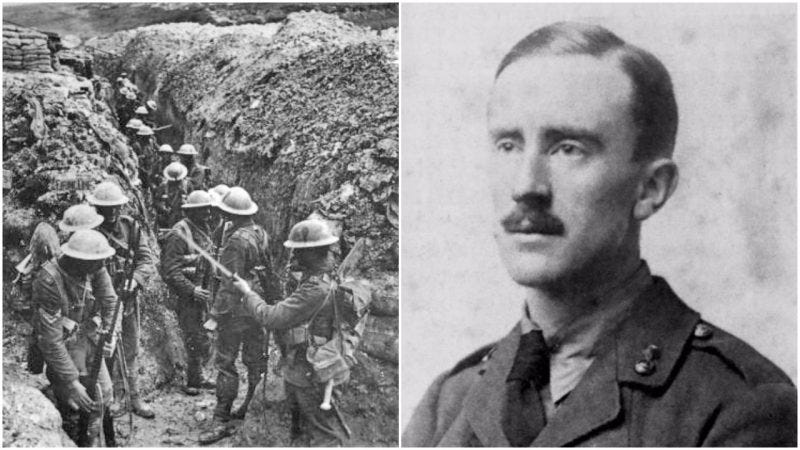

However, it is my solemn view that a man who witnessed the savage destruction of human lives in the trenches of the First World War has every right to look at the advances of modernity and cry foul. No reasonable person could view the bleakness of Flanders Field, France, even in grainy 1919-definition photograph, and then say with a straight face that technological advancement is an unflinchingly good thing.

So yes, Tolkien says that fairy-stories are good in part because we can Escape from the glare of electric street-lamps and because old buildings are prettier. Frankly, I don’t think one must agree with Tolkien’s neo-Ludditism to still love fantasy, nor do I think fantasy (or fairy-stories) must necessarily embrace an anti-industrialist mindset in order to achieve wondrous effects.3

In any case, this is a debate for another time, because this is largely beside Tolkien’s point! Remember the analogy of the Prisoner and the Deserter. The Deserter will look at the world and seek to flee; indeed, an uncareful reading of Tolkien’s thoughts on technology will look like Flight. But the Prisoner looks at reality and seeks to experience something which he lacks. That’s what Tolkien is pointing us toward.

By embracing an archaic, pre-modern, un-electric Secondary World, the fairy-story can actually focus on more important aspects of reality which we might “lack” because of our technocratic Robot Age.

For my part, I cannot convince myself that the roof of Bletchley station is more “real” than the clouds. And as an artefact I find it less inspiring than the legendary dome of heaven. The bridge to platform 4 is to me less interesting than Bifröst guarded by Heimdall with the Gjallarhorn. [...]

Much that [critics of fairy-stories] would call “serious” literature is no more than play under a glass roof by the side of a municipal swimming-bath. Fairy-stories may invent monsters that fly the air or dwell in the deep, but at least they do not try to escape from heaven or the sea.

Undistracted by the technology of the setting, fairy-stories can help us see immaterial realities, which are no less real for their immateriality: things like love and relationships and duty and life.

Fairy-stories are not concerned with timely inventions. They are concerned with timeless realities.

“The march of Science, its tempo quickened by the needs of war, goes inexorably on... making some things obsolete, and foreshadowing new developments in the utilization of electricity”: an advertisement. This says the same thing only more menacingly. The electric street-lamp may indeed be ignored, simply because it is so insignificant and transient. Fairy-stories, at any rate, have many more permanent and fundamental things to talk about. Lightning, for example.

(Note there the connection between new technology and the organized destruction of human beings). Instead of an uncritical celebration of “advancement”, a medievalist or naturalist setting can help us appreciate things which are more permanent than the so-called “inexorable” advances of our present day. Escape is not a mere curmudgeonly escapism from new-fangled devices, it is instead a call to focus on the beauty and majesty of this world. Escape of this kind dovetails with, and bleeds into, Recovery.

Tolkien also goes on in this section to heavily criticize science fiction, at least the sort of stories where men, freed from present-day technological restraints…

…will use this freedom mainly, it would appear, in order to play with mechanical toys in the soon-cloying game of moving at high speed. To judge by some of these tales they will still be as lustful, vengeful, and greedy as ever; and the ideals of their idealists hardly reach farther than the splendid notion of building more towns of the same sort on other planets.

The failure of such stories is not in their fascination with tech, though Tolkien clearly dislikes that personally, it is in their failure to engage with deeper questions about the human condition.4 The fairy-story not only focuses on natural things, but also spiritual things.

Lastly, Tolkien concludes this section by saying that even if the appeal of fairy-stories was purely about an archaist romanticism, that would be okay too! Fantasy would still have value.

And if we leave aside for a moment “fantasy,” I do not think that the reader or the maker of fairy-stories need even be ashamed of the “escape” of archaism: of preferring not dragons but horses, castles, sailing-ships, bows and arrows; not only elves, but knights and kings and priests. For it is after all possible for a rational man, after reflection (quite unconnected with fairy-story or romance), to arrive at the condemnation, implicit at least in the mere silence of “escapist” literature, of progressive things like factories, or the machine-guns and bombs that appear to be their most natural and inevitable, dare we say “inexorable,” products.

Escaping Hardships & Ancient Limitations

Aside from his polemic against modern technocracy, Tolkien also explains that there are other things in life which are worth Escaping.

There are other things more grim and terrible to fly from than the noise, stench, ruthlessness, and extravagance of the internal-combustion engine. There are hunger, thirst, poverty, pain, sorrow, injustice, death.

These are the walls that bind the Prisoner, and it is not wrong to seek Escape towards higher goods. While we ought to be suspicious of mindless flight that pulls us away from our duties and towards a denial of reality, that is entirely different from a desire to change one’s circumstances.

That desire, if it aims at what is good, has a name: hope.

Good Escape can uplift the soul, hone the mind, and give us hope.

“And even when men are not facing hard things such as these,” writes Tolkien,

there are ancient limitations from which fairy-stories offer a sort of escape, and old ambitions and desires (touching the very roots of fantasy) to which they offer a kind of satisfaction and consolation. Some are pardonable weaknesses or curiosities: such as the desire to visit, free as a fish, the deep sea; or the longing for the noiseless, gracious, economical flight of a bird, that longing which the aeroplane cheats, except in rare moments, seen high and by wind and distance noiseless, turning in the sun: that is, precisely when imagined and not used.

He also mentions “the desire to converse with other living things,” namely animals or trees. For “other creatures are like other realms” which we cannot access. Such barriers can disappear in the land of Faërie, and just as men who cannot travel far but “must be content with travelers’ tales,” fairy-stories can help us experience these curiosities and give us that “kind of satisfaction.”

Here again we see the link between fantasy and myth, for the desires to soar in the sky, to walk the ocean, or converse with beasts are as old or older than writing itself. We see these desires in Icarus, in Poseidon, in Melampus.

Death and Deathlessness

And lastly there is the oldest and deepest desire, the Great Escape: the Escape from Death.

Tolkien’s ideas regarding life after death (i.e. his fervent Catholicism) make an appearance later in the essay, but at this stage he only gives a brief statement about fairy-stories’ “escapism” surrounding death.

He says that many fairy-stories do indeed convey a “fugitive spirit” regarding death (think: Flight of the Deserter). “But,” he says, “so do other stories (notably those of scientific inspiration), and so do other studies.” If there is error to be found in wanting to escape death, it is not an error reserved for Fantasy.

Tolkien even points out that fairy-stories just as often take the opposite view:

Few lessons are taught more clearly in [fairy-stories] than the burden of that kind of immortality, or rather endless serial living, to which the “fugitive” would fly. For the fairy-story is specially apt to teach such things, of old and still today.

Tolkien says no more of death at this point, but we can trace his thought from here to the legendarium of Middle-Earth, where Death is the Gift of Eru Ilúvatar to Man and the envy of the Elves.

A Mark of Quality or of Kind?

As with all aspects of fairy-stories, Escape’s endorsement of reality is not automatic within fantastical tales. Rather, Escape is a consequence of Fantasy done well. In my view, the most common error in reading “On Fairy-Stories” is believing that Tolkien thinks fairy-stories (what we might extrapolate into the modern “fantasy genre”) must by definition be infused with the same values of Escape that he extolls. I don’t believe that Tolkien holds Escape (or Recovery or Consolation) as things which must be present in order for a piece to qualify as Fantasy (i.e. a fairy-story); however, it is abundantly clear that Tolkien thinks these things must be present for the Fantasy to be “good,” and that the presence of these things come from a well-told story and a well-built world.

The well-crafted fairy-story will provide a true sense of Fantasy, it will help us Recover a properly wondrous view of our own world, and it will help us Escape the evils which befall us and bring us towards a truer joy.

That joy, in Tolkien’s view, is “the mark of the true fairy-story.” And it is that joy—Consolation—which Clifford will unpack for us next week.

✹ ✹ ✹

Thank you for reading part three of this series. The fourth and final part will publish next week, and when that goes live I’ll link it here.

And remember! We’re going to do a round-up of the best comments from you, our readers, likely with some of our own thoughts thrown in, so don’t hesitate to join the conversation below (or over on Notes). We want to hear from you!

All Parts:

Part 1: The Art of Fantasy

Part 3: Embracing Reality by Escaping to Faërie (this post)

I recommend you subscribe to Clifford’s publication, Past the Dragon. It’s well worth reading. I highly recommend Clifford’s work, like his recent take on the eras of fantasy literature. I’m thrilled that we can work together to bring you this series.

If you like what you’ve read here you can help me write more of it by liking, commenting, or sharing this piece.

✹ ✹ ✹

This is also why critics of the genre should read “On Fairy-Stories,” so that even if they don’t come to like fantasy personally, they can hopefully come to appreciate its strengths.

Considerations of English class hierarchy do very little to dent my love for Tolkien or for his works, but it is worth noting that class divisions and a romanticization of them certainly come through in Tolkien's fiction. Eh, I don’t know, maybe I’m just American.

As an aside, I happen to largely agree with Tolkien’s curmudgeonly thoughts about technology, it’s just that I think this part of his argument here, as it relates to fairy-stories, is weak.

Like Tolkien and Tech, Tolkien and Sci-fi is another whole discussion, beyond the scope of this series. But also: we should remember that Tolkien wrote the bulk of this essay in 1938, long before the likes of Ray Bradbury, Philip K. Dick, or even Frank Herbert, and all their dystopian visions. Such stories often have even stronger condemnations of technology's effect on humanity than the sheer horror of a brick Mill on the Brandywine.