Quick preamble: some illness or another has made its way through the Falden household this week and put me out of commission for a while. As a result, this post only covers about half of what I have to say on this topic, and its a bit shorter than usual. So I am calling this post merely a “Part One” of… at least two.

My illness also incentivized me to muse on a topic that I have spent an inordinate amount of my life thinking about and studying: the development and evolution of arms and armor.

In other words, I’m going full nerd on y’all.

More specifically, I’m going to explain in broad terms the dynamics that determine what kit (what combinations of arms and armor) men carry into war.

From a worldbuilding and storytelling perspective, these are the dynamics and rules that determine what your heroes and adventurers might have at their disposal when they go fight the Big Bad Evil Guy. It is also—in my own personal and non-binding opinion which you are not required to follow—the rules that determine when a fantastical story leaves the realm of the grounded and immersive and veers into wish-fulfillment and cringe. (In my opinion (which you can disagree with and discard)).

So grab your cudgel and put on your kettle hat. We’re going to war.

What would YOU bring to combat?

Let’s start with a hypothetical, and put ourselves in the shoes of someone who’s about to march off to war or onto some big quest. Let’s say that in a few weeks time, you will have to leave home and face danger; you know you’ll be in combat against people who are going to try and take your life; you know that to survive, you will have to kill them (or maim them or otherwise destroy their ability to kill you) first.

Now let’s leave aside all the reasons why you might have to do this and the other psychological and physical ways you might try to prepare yourself. Let’s hone in on one question: what are you bringing?

More specifically, what do you want in your hands when that moment of combat comes? What kind of protection will you bring?

I’m willing to bet you and I have the same answer: the best weapons and equipment possible.

Simple, right? Your life is on the line; you probably wouldn’t pinch pennies or phone it in. You’re going to spend time thinking about what to bring and why, and then do your best to outfit yourself.

Here’s the thing though. That guy who’s gonna try to kill you? He’s thinking the same thing. Soldiers—all soldiers—go to war carrying the best equipment possible.

“Possible” & The Potential for Upgrade

I’ll admit that the word “possible” is doing quite a lot of work in that sentence above. It’s not a matter of soldiers always being equipped with the best. Far from it! It’s rather that few people will go into danger without the best things that they can get their hands on.

In the present day as in all of history, a warrior’s kit is largely determined not by what’s available in general, but by what’s available to them personally. Technologies, materials, cultures, and above all economics do most of the narrowing of a warrior’s options. By the time anyone sets out to war, basic realities will mean there aren’t that many options for them when it comes to what they can bring.

The limited choices at the common soldier’s disposal is one reason why states will supply recruits with standardized equipment as soon as they are rich and organized enough to do so.1 Such a state can generally get better kit for their poor, common farmers than the farmers can get for themselves.

At the same time, however, whenever an individual soldier has the financial capability to equip himself he will do so, and he will inevitably end up with better equipment than what the common recruit is given.

Even in U.S. military operations today, civilian private military contractors (aka PMC’s / mercenaries) tend to have much better personal equipment than their formal military counterparts. After all, who’s going to put a higher value on that contractor’s life: Uncle Sam or the man himself?2

It is a simple fact of history that the richest individuals on the battlefield tend to be the best equipped. Given that in many societies personal martial skill was the most straightforward path to getting those riches—or, in the case of medieval knights, one’s riches allowed a man to have the luxury of training for combat from a young age—this also meant that the best equipped soldiers were usually also the best soldiers man-for-man, all other things being equal.

That vicious cycle of real-life min-maxxing in turn explains a lot of the dynamics of the premodern battlefield and its over-emphasis on bands of elite warriors (like a king‘s bodyguard troops, chivalric knights, or a warlord’s personal retinue of followers).

In a future post, I’d love to explore the many ways that economics and culture drive the choices (and lack of choices) available to common foot soldiers across the Middle Ages. If and when I make another post on that, I’ll link it below. But for now, I’ve gone far afield from what I’d like to discuss: the development of weaponry and why a lot of fantasy weapons (in video games, in movies, in fan art, and yes, in novels) don’t really make much sense at all.

Tactical Co-Evolution

Remember our hypothetical: grab what you can because we’re going to war. You and I are both going to spend a lot of time thinking about our options and we’ll march to battle with the best possible equipment.

Our enemies, crucially, will do the same thing.

When we get to the war camp we’ll be entering a new sort of society, one where the whole of our world is ordered towards one thing: fighting. The one thing you and I will have in common with every other person at this war camp is that we’re going to fight and they too will have sourced the best equipment they can. In all likelihood, there will be some conversation about equipment, and how to best gain an edge in combat.

Our enemies, crucially, will do the same thing.

In other words, there will always be some element of an “arms race” happening. The particular kit that soldiers will bring to battle will be rooted in a particular time and place; the kit will depend upon the types of threats those soldiers expect, the sort of enemies they expect to face, the sorts of tactics they are prepared to deploy against those enemies, and the level of training they may or may not have.

Over time, fighters will settle upon a set of agreed upon tactics and strategies that are best suited to victory (and survival). Those tactics will arise from lived experience, because those who don’t understand the basics of “normal” combat end up dead. Veterans will take time to teach raw recruits what that “normal” combat will be like because survival in combat depends on your comrades. A school of thought will develop and persist, a set of agreed-upon, informal doctrines that will increase the likelihood that you survive and the other guy does not.

Then, after combat, soldiers will naturally reassess their needs and make necessary changes.

And their enemies, crucially, will do the same. The “normal” thus changes over time. The “others guys” will develop and adapt their own school of thought to thwart yours. They will create counter-tactics to your tactics, and then you’ll have to develop counter-tactics to their counter-tactics, and so on.

This is what we call “tactical antagonistic coevolution,” a phrase borrowed from evolutionary biology. Tactics are constantly evolving because they are always locked in an antagonistic relationship.

Anyone who has spent time playing competitive games (e.g. PvP video games, chess, or even card games like Hearts and euchre) will recognize this dynamic. New players would do well to learn the “meta” of a game unless they want to lose all the time.

That “meta” will persist until someone finds a way to thwart it. If you can be the first to subvert the meta, then you’ll have an advantage over every other player because every other player is playing the meta. And this is exactly the kind of tactical innovation and “edge” that soldiers look for when they’re outfitting themselves for combat.

In a video game, outside forces might disrupt the meta as well; an update to a certain item’s stats, or new content being added to the game. In war, the meta gets disrupted by technological innovation, societal changes, and just about every other major cultural force operative in history.

The tactics of an army, down to the specific pieces of equipment that every individual might carry into battle, is developed specifically within a given “meta.” These things evolve only because of the antagonistic relationship they have with particular, specific enemies.

Oftentimes the person you are most likely to face on the battlefield actually has a kit that’s remarkably similar to yours, because you are likely to face someone from a similar economic and cultural milieu—from within the same meta.

But when the meta gets disrupted—when there’s been an antagonistic evolution against your tactics—there could be catastrophic consequences for you, for your fellow soldiers, and for your society writ large.

One final note. It’s probably clear from everything I said above, but I want to say it explicitly: within antagonistic coevolution, tactics are both a cause for technological change and also an effect of technological change. You’ll change your weaponry to best suit your planned tactic, but you’ll also change your tactics based on the available weaponry.

What Does This Mean For Kit?

Let’s embed the concept of tactical antagonistic coevolution into actual time periods with specific examples. In other words, let’s look at some weapons.

When we look at these historical artifacts under the assumption that the people of the past knew what they were doing and did not want to die, we can pretty easily work our way backward towards specific tactics and even into a “meta” of warfare in a given period.

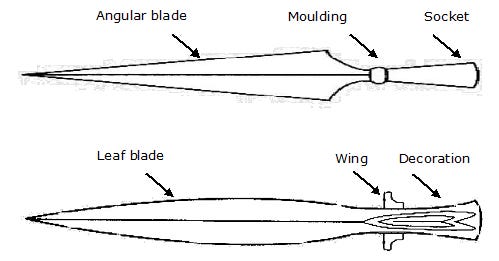

Consider, for instance, these two common types of spearheads that date to Viking Age Europe, ca. 750-1050 AD. For reference, these types of spearheads often ran around 50cm (19-20 inches) long in total.

These two types of spears existed alongside one another, but anyone who has more than one kitchen knife understands that different shaped/sized blades have different uses.

The top blade is rather… focused. It’s pointed geometry also betrays a singular (pointed) purpose: stabbing. This might seem entirely obvious since, you know, it’s a spear, but consider the fact that the one below it is not as angular and pointed. But the top spear can really only cut anything if the point is being driven into the target. Most importantly, the angular blade is also much thinner at the point, so it needs less force to drive into a target. More force arrives over a smaller area. Considering the other material “meta” of the day and age, we can see that spearhead would be more effective than its above counterpart at punching through the best armor available in Europe at the time: chainmail. This is undoubtedly a weapon of war, made with malice aforethought, designed to kill men, even if they are wearing the best armor available.

The bottom blade is leaf-shaped. Unless I’m misinformed, it’s a much more common archeological find for the period. The leaf-shape may be far worse against chainmail, but the vast majority of people did not wear chainmail. The most common enemy is one who has, at best, cloth armor. Consequently, while most of the force is still directed into the tip, the blade widens more quickly to really open up a person’s… person. Instead of maximizing the depth of the wound, the leaf blade maximizes the overall size of the wound. The wider blade means more stopping power. It packs more of a punch. The curved blades also mean it is not as useless to swing the blade side-to-side like an ax; such an action is far from optimal, but it’ll do more damage being swung than the angular blade.

Aside from the difference in shape, there are also “wings” or “lugs” near the socket. If we again assume that the crafter wasn’t stupid, we can realize this isn’t merely decoration: they have a purpose. Actually, they could have several, none of them contradictory. Oftentimes these wings were much, much longer, forming a larger crossbar. Why would you need such a big set of lugs? You’d think that if you’d already put nineteen inches of steel through someone, they would probably stop whatever they were doing. Would you need to put a crossbar on it to make sure they stay back? Well, if that “someone” were a charging boar or a galloping horse, then yes you very well do! The presence of wings on a spearhead thus indicate that the bearer expected to come face to face with a big and heavy animal coming straight at him, whether that be a wild beast or a mounted warrior. Furthermore, the wings could be used to parry or lock someone else’s spear.

In total, the leaf-blade spear denotes a person who wants a versatile weapon, likely used by common infantry against common infantry (no chainmail), likely in tight formations (where the curved blades could jerk side to side a bit once things get close and you’ve already missed a man’s head) against other spear-bearers (so you could parry their spear shafts with your lugs, and let the guy next to you stab your opponent).

And oh look that’s exactly what we find in the pictorial evidence of the period.

The men above are mounted; you can see the little horse-heads peeking between the shields. Frankish infantry formations are barely present in the pictorial record, though we have some literary descriptions, and other evidence of individual Frankish infantrymen, like below.

In the above scene, that’s one of King Herod’s soldiers committing war crimes. However, it was (and is) a common artistic motif to depict past events—especially Biblical events—with clothing contemporary to the artist (and the presumed audience). This soldier of the Herodian Kingdom is thus depicted like a 9th century Frankish soldier. Same as below:

Then, contemporary with our Ottonian German cavalrymen, we have this, from Italy.

And a century after that, from Catalonia…

And there we have it: a simple diagram of spearheads and we can then reasonably posit an entire combat system from it. Even tiny details like lugs on a spear matter, because they reflect decisions made by people equally reasonable to ourselves and equally unwilling to die.

Of course, we don’t need to speculate that much from single data points because we also usually have plenty of other pictorial, material, or literary evidence (like the battle scene above). But there’s still a lot of speculation because no source will answer everything, and anything put to parchment will have some level of bias. After all, these things are not written so that you and I can nerd out about spearhead shapes.

But as I recently read in a book by archeologist and historian Neil Price:

… history is nothing if not a suppositional discipline, sometimes akin to a sort of speculative fiction of the past.

Wrapping Up

Alright folks, I have to wrap up, but I’m not remotely through everything I want to say on this topic. Alas, there’s only so much space in a newsletter and only so much my head-cold-stymied brain can write.

So I am calling this Part 1.

Click here for Part 2, where I’ll give more examples, more developments, and begin unlocking lessons and takeaways for the fantasy genre. In particular, I’ll explain why fantasy weapons often… don’t make any sense.

Thanks for reading, and see you next time.

✹ ✹ ✹

If you like what you’ve read here and want me to keep making stuff like this, you can help me do that by liking, commenting, or sharing this piece. You can also see all my writing by visiting this page.

✹ ✹ ✹

✹ ✹ ✹

No equipment was ever truly standardized prior to industrialization. Even in cases where we can do things like list out all the basic equipment of the 'typical' Roman legionary, there was a huge variance in overall quality of pre-modern soldiers' kits.

Old Friend Dunmore reminds me that modern military procedure is the assignment of every piece of kit to individuals, so your rifle is yours, your truck is yours, your helmet is yours. This way, you’ll take care of it, learn its quirks, and prevent it from failing.

Very much eager for the next part of this. I love reading about stuff like this AND it’s useful knowledge

Very well-researched and interesting! I eagerly await the next part.